End of Line(rs)

- Jacob Lyngsøe

- Feb 17, 2023

- 16 min read

Updated: Jun 7, 2025

Friday, 2 May, 1952

At London Airport (as Heathrow was once called) it is a cool and drizzly afternoon, but by 3pm the rain has let up and a few rays of sunshine are piercing the grey cloud cover. A lone white-and-silver jetliner, call sign G-ALYP, is taxiing across the damp tarmac towards the runway. It is a de Havilland DH106 Comet from British Overseas Airways Corporation (B.O.A.C) - the world’s first commercial jetliner. With its mirrored aluminium fuselage, conical nose, swept wings and integrated turbojet design, it looks sleek, powerful and futuristic and the sight of it draws cheers from curious onlookers along the taxiway.

Reaching take off position, it turns and aligns with the runway, then comes to a halt as the pilot awaits final clearance. The onlookers fall silent, caught up in the moment. Moments later the engine rumble grows to a powerful roar, the exhausts blow water mist off the tarmac in billowing fumes and the Comet lurches forward. The sleek liner accelerates nimbly down the runway. At 3:12pm she lifts off into the cloudy skies, taking 36 passengers to Johannesburg, kicking off the ‘Jet Age’ and ushering in the end of the line for the transoceanic ocean liner business.

A century of cruising

Cruising had at this point existed as a commercial leisure activity for more than 100 years. It came about shortly after the first engine-powered passenger ships enabled regular scheduled liner traffic in the mid-19th century and grew into a symbiotic relationship with the passenger shipping industry. As leisure travel grew more popular and shipping grew safer and more comfortable, shipping companies came to regard cruising as a regular and profitable sideline, sending their ocean liners cruising whenever there was an off-season or a profitable occasion, ensuring that their ships would remain operational and profitable year-round. Cruising formed a perfect on-again, off-again relationship with passenger shipping, interrupted occasionally by geopolitical conflicts and financial downturns, but almost always coming back stronger.

Twilight of the ocean liner

Over the decades, ocean liners had multiplied their tonnage, passenger capacity and performance many times over and transformed radically from cramped, spartan and risky adventures at sea to floating palaces of leisure, luxury and comfort and cruising had grown with them, both conceptually and numerically. But in a century of abundant liner travel, cruising had never found neither reason nor opportunity to divert itself from the passenger shipping trade and grow into an industry in its own right, and that was now about to become a major challenge to its continued survival. With the flight of the first commercial jetliner ocean liners had arrived at the twilight of their era, facing the same fate as the horse carriage and the telegraph and unless cruising found a way to survive on its own business terms, it might go the same way.

Across the Pond

Transatlantic flight was pioneered all the way back in 1919 when British airmen John Alcock and Arthur Brown crossed the North Atlantic in an open-cockpit Vickers Vimy biplane. Yes, I know - you immediately thought of Charles Lindbergh's flight of 1927, but plenty people had actually flown across the Atlantic before he came along. Lindbergh's big achievement lay in making the first non-stop, solo flight that landed where he had said it would (Paris), instead of just landing / falling randomly out of the sky wherever the pilots found firm ground. However, flying did not become a mainstream commercial service until after World War II. Even then it was hardly a swift nor comfortable affair: using converted WWII long-range aircraft the journey across the Atlantic took around 15-20 hours with multiple stops for refueling and the cramped, unpressurized cabins made the experience less than comfortable with constant droning engine noise and vibrations, fluctuating temperatures, frequent turbulence at lower altitudes and minimal space to move about. Subsequent developments of new commercial aircraft types would improve the experience but the game would not truly change until the Comet came along; with its pressurized, airconditioned cabin, reclining seats and first-class catering, it offered a smooth, quiet and very comfortable non-stop flight and the two pairs of Halford H.2 Ghost turbojet engines delivered you to your destination in only half the time.

The Comet would not be deployed for transatlantic service until 1958 - in part because an unfortunate hidden design flaw caused two of them (G-ALYP being the first) to spontaneously disintegrate in midair in 1954, killing everyone onboard and teaching the aviation world about the hidden dangers of metal fatigue in jetliner airframes. When it finally did arrive in the skies above the Atlantic - now in a safe and improved version - it found fierce competition from its newly introduced American counterpart, the Boeing 707, both plane types cutting the travel time in half and setting new standards for airborne comfort and luxury on the Transatlantic circuit.

The Jet Age Drain

Regular travelers on the ocean liners were quick to ask themselves why they should devote 4-5 days to a seaborne crossing when they could arrive at their destination in 6-8 hours with a quite decent level of comfort and luxury. To begin with it was only the first-class passengers who abandoned the ocean liners and became the vaunted ‘jet set’. But as aircraft technology swiftly evolved, jetliners became bigger, more efficient and more plentiful. Ticket prices dropped, economy class evolved (that actually started as early as the 1940's), flight networks grew, air travel became commonplace and more and more travelers switched from ocean to air to a point where the mighty liners crossed the oceans with more crew than passengers onboard. By 1970 transatlantic passenger shipping had gone from a near-monopoly to carrying only 4% of passengers across the Atlantic.

The Final Decade

The 1960's became the decade when most of the great ocean liners fell by the wayside: SS America – sold in 1964 to Chandris Group who turned her into the cruise ship Australis. RMS Queen Mary – sold in 1967 to Long Beach where she remains until today as a floating hotel. RMS Queen Elizabeth – sold to Hong Kong as a floating university in 1968 but was lost to fire during conversion in 1972. SS United States – mothballed in 1969 (and rusting away quietly to this day in Philadelphia). By 1970 only the SS France (barely 10 years old at the time) was still hanging in there, but by 1974 she too bowed out and got laid up in Le Havre. And those were only the biggest and most famous of them – a much larger fleet of smaller and lesser-known ocean liners were also out of a regular job.

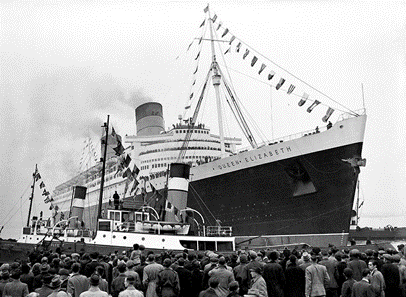

Top left: SS United States. Top right: RMS Queen Elizabeth.

Middle left: SS America. Middle right: RMS Queen Mary. Bottom: SS France

Switch to Cruising

During this period shipping companies increasingly try to counter the drop in crossings by switching their liners to cruising roles, but the mass market is not there yet. Their client base was large and loyal enough to fill the occasional off-season cruise offering when crossings were still the primary business, but far from big enough to fill all their ships full-time when cruising was all the business there was. Despite a successful interwar period in which both England and the US saw a considerable increase in interest for cruising, it remained a rather obscure leisure phenomenon that people had likely only heard of or would even consider if they lived in or near a cruise port or had a particular affinity for sea travel. The rise of mass media would help in growing the clientele, but it would still take until the 1970's for the 'cruising trend' to reach something like general awareness or ubiquity in the main source markets.

Under-tapped source markets aside, another challenge to just indicriminately switching idle ocean liners to cruising roles was that ocean liners do not make the most ideal cruise ships. This would not have been a surprise to anyone in the business - that realization had been around since the 1890's when Hamburg-Amerika Lines Albert Ballin first noted that while ocean liners can function satisfactorily as cruise ships, they are ultimately not the most ideal vessel for the task (read The White Princess). This may seem nonsensical to those of you who keep confusing 'ocean liner' with 'cruise ship' but there are in fact considerable differences between the optimal designs for both ships.

Liners v. cruise ships

Ocean liners are built for high-speed passenger transit between point A and point B - usually between continents and usually in a straight line (hence 'liner'). For this purpose they have big, powerful engines to push them through any kind of seas and keep to schedule and a sturdy and heavy construction for stability, momentum and weather endurance, including elements like long tapered hulls with knife-like bows, deep drafts and high freeboards. Ocean liners tend to have relatively little outdoor deck space for guest use because large portions of it are working areas, cluttered with loading cranes, hatches, winches, ventilators etc. and what is left is often enclosed or sheltered from the elements and not particularly suitable for enjoying the outdoors. Their interiors - while undoubtedly luxurious and comfortable - are designed to maximize occupancy and only offer the minimum amount of leisure space and activities needed to while away the duration of an ocean passage (which at this point in time was around 4 days for the Atlantic).

Ideal Cruise Qualities

But all those essential features of ocean liners are no good on an ideal cruise ship. Conceptually, cruise ships are meant for meandering sightseeing trips at a leisurely pace, often in a full circle, taking passengers back to their starting point. To do that economically they require less powerful but more fuel-efficient engines, designed for more varied levels of propulsion (incl. frequent starts and stops) and constant maneuvering. Their construction needs to be lighter (to reduce fuel consumption) and does not need to be as weather-resistant as their ocean liner cousins (as they are not meant to operate in bad weather regularly). The optimal hull design for cruise ships is more rectangular than tapered (to maximize cabin standardization potential) with shallower drafts (for accessing smaller ports and shallow waterways), lower freeboards and shorter bows (as there was no need to protect from massive waves). Cruise ships need to be able to offer lots of outdoor leisure space as the whole point of their existence is to allow guests to enjoy delightful tropical climates and their interiors have to be crammed full of leisure and entertainment options to keep guests busy, entertained and spending money for a lot longer than 4 days.

So the challenge of converting ocean liners to cruising roles effectively and profitably was that 1) their high-performance, fuel-hungry engines and heavy build made them uneconomical, impractical and maintenance-heavy for cruising, 2) their size, draft and build made it difficult for them to access / navigate the traditionally smaller cruise ports and 3) their interiors just did not offer guests enough to do during the longer cruises. To begin with, the novelty and excitement of a sea voyage would easily trump 3) but as cruise guests grew more experienced and discerning and the market innovators started tailoring their newbuilds more and more to the cruise ship ideal, it became a real handicap to the older generation. Many classic ocean liners rendered obsolete by the jet flight revolution did enjoy decades of cruising success, but never without addressing these three points with technological or conceptual solutions, and all cruise newbuilds constructed from the late 1960's onwards would leave the liner format behind and fully embrace the cruise ship format.

Despite the 1960's becoming the decade when the big ocean liners ceased operations, one very notable exception to that trend also illustrates how operators tried to bridge the gap between liner and cruise ship. In 1964 Cunard decided to press ahead with plans to construct a new large ocean liner to replace the two ‘lost’ Queens. They knew full well the days of the liner were numbered, yet refused to relinquish their traditional role as provider of North Atlantic Passage so the new ship had to be as perfect an ocean liner/cruise ship hybrid as could be.

The last of her Kind

They made her functionally dual-purpose, energy-efficient, all-weather-compatible, capable of transiting both the Panama Canal and the Suez Canal and they named her Queen Elizabeth II. She launched in 1969 and settled into a routine of summer Atlantic crossings and winter cruises. The QE2 became that very last of the great ocean liners – a symbol of nationhood and proud seafaring traditions as ocean liners used to be – that was simultaneously also a renowned and efficient cruise ship. Even in the age of the aircraft, she was able to keep transatlantic crossings going thanks to a unique mix of monopoly, prestige, nostalgia and tradition that kept passengers booking her. During her 39-year dual-purpose career (the longest career of any Cunard ship ever), she sailed more than 9 M km / 5.6 M mi (or 12 round-trips between Earth and Moon), carried more than 2.5 million passengers and completed 25 world cruises and 806 transatlantic crossings. She retired in 2008 and is now a floating hotel in Port Rashid, Dubai. But that was a narrative detour for a very special lady – let's get back to the showdown between air and sea.

No more Piggybacking

As the big liners bow out, smaller liners find a new life servicing long-distance shipping lanes that jetliners still do not have the range or volume for, like Asia or Australia. Others are scrapped, mothballed, switched to cruising roles or sold to seafaring nations with less developed air travel. All but the largest of ports gradually lose their regular transoceanic services and as the ships (and their associated infrastructure) disappear, so does the local access to regular off-season cruising activities. From having a foothold in many large Atlantic shipping ports, cruising had now effectively become homeless. The days of piggybacking on the existing ocean liner network are over. Anyone who wanted to cultivate a purebred cruise business would now have to go in and establish a base of operations on the ground first … but where would that be?

Cruise Hotspots in America

For the United States, that turned out to be Miami, Florida - surprisingly a port with little to no pre-existing transatlantic liner traffic. Through a mix of prime location and climate, great leisure scene and random chance, this sleepy little South Florida port went on to become Cruise Capital of the World in just a few decades. The 1950 introduction of year-round cruising with the Nuevo Dominicano (as described in Genesis Miami) became the inciting incident for the American cruise industry and created the conditions for a year-round cruise industry to evolve just in time to take full advantage of the idle ocean liners. While Miami became the Cruise Capital, pockets of cruise activity still survived in the other 'corners' of continental USA - in the northern latitudes there was seasonal cruising to Canada/New England and Bermuda out of Boston and New York in the East and to Alaska out of Seattle in the West. Once those seasons ended the ships would migrate south and join the ships doing year-round Caribbean cruising out of Florida in the East and Hawaii / South Pacific and Pacific Mexico / Central America cruising out of California in the West. This particular seasonal / regional pattern of American-based cruise infrastructure and business holds true to this day.

The American Way

One interesting observation of the US cruise business vs the European one is that none of the US passenger shipping companies that initially pioneered cruising managed the conversion to full-time cruise lines, whereas in Europe almost all the cruise lines formed from time-honored passenger shipping companies, like Cunard, P&O, North-German LLoyd, Holland America etc. But early American shipping pioneers like the Ward Line, Grace Line, Matson Line, Furness Bermuda Line or Peninsular & Occidental did not manage the same transition - instead they turned to cargo shipping only or went out of business all together as airliners highjacked their passenger clientele and the emerging cruise lines tapped their leisure clientele. The big name American players in the cruise industry, Like Carnival, NCL, Princess and Royal Caribbean are all the result of individual entrepreneurs from the shipping industry starting from scratch on focused leisure operations, rather than building on an established shipping brand... in other words, very much in the 'American Way', and their rapid rise and massive success undercut the market for the traditional shipping companies.

Meanwhile in Europe

The continental cruise market underwent much the same transformation / consolidation process. By the early 1950's the continent was already experiencing a decline in the post-war immigration boom to the US and the advent of air traffic only hastened that decline, resuting in a lot of ships with nothing to do. The number of departure ports for ocean liner traffic shrank and the transformation from ‘liner traffic’ to ‘leisure traffic’ was pioneered in the few remaining hubs by shipping operators shrewd / lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time and have the experience with seasonal cruising needed to permanently gear their ships from line to leisure. Mediterranean ports like Barcelona, Civitavecchia (gateway to Rome) and Pireaeus (gateway to Athens) rose to prominence due to their convenient location in or near major tourist destinations with international travel access (and because a majority of existing shipping companies were either Italian or Greek). In the Northern part of the continent only Britain retained an active cruise market after the war and Southampton (once again) became a major hub for British-based cruise lines. Due to the Northern latitude this became by necessity a seasonal operation with summer activities around the Baltic / Norway, Northern Europe and Atlantic Islands and winter activities around Southern Europe, the Mediterranean and Atlantic Islands, often seeking out seasonal turnaround hubs in the region and letting guests fly in from the dreary British winter weather. A pattern and infrastructure of European cruising that likewise holds true to this day, though many more players have by now joined the fray.

European Players

The players on the continental market came primarily from the existing passenger shipping industry; Cunard, P&O, Hapag-Lloyd, Holland-America, Celebrity (formerly Chandris) and others who saw a chance to convert their liner business to cruising. Some also started as post-war offshoots to cargo shipping lines (MSC and Costa, most notably or the long defunct Italian Home Lines and Sitmar Cruises). But competition was tough and the leisure cruise market flighty and seasonal. For every shipping company that succesfully managed the transition from liner to leisure traffic, many others fell by the wayside. Once great companies like Italian Lines, Swedish American Lines, Typaldos Lines, Epirotiki Line, Royal mail Lines, Blue Star Line, French Line and many others were weeded out along the way and now exist only in cruise history footnotes. But while many of the brand names in European cruising have not changed over 150 years, ownership has. In an ironic twist of history those cheeky American upstarts that joined the cruise game so late now own most of the European cruise brands that predate them. Carnival Corporation has long since absorbed Cunard, P&O, Holland America Line, Costa Cruises and others and Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd owns Celebrity Cruises, Azamara, Silversea, TUI Cruises and Hapag-Lloyd.

An unexpected Helper

But the industry would never have transcended local obscurity into global phenomenon if it had not been able to expand its source markets considerably, meaning attract people from a lot further afar than the few isolated hotspots they were operating from. The one thing that allowed the cruise phenomenon to grow steadily over decades was ironically the very same thing that almost killed it off to begin with; the airliner. The same planes that made the liners obsolete, could now be used to feed passengers from all over the world to the fledgling cruise hubs of both continents. Flying was no longer the preserve of the elite and the upper class - economy travel had opened up the skies to Everyman. As local access to leisure cruising in many smaller ports waned, airborne access to the cruise offerings of the major hubs increased and the passenger supply kept flowing ... and growing.

Cruise lines on both sides of the Atlantic quickly realized that if you packaged both the flight and cruise together, it made a lot more attractive and convenient leisure package (and it gave them a better way to hide their profit margins), so before long an ‘air package’ became a standard offering and then ‘stay packages’ too for additional nights pre- or post-cruise in local hotels, followed by countless other add-on services and experiences. And just like that cruising had become a truly diversified leisure product (bearing in mind that the phrase 'just like that' still characterizes a period of more than 2 decades).

The Jetliner Contribution

It's been 70+ years since that first airliner took flight and while it undeniably heralded the end of the line for ocean liners, it also paved the way for the cruise phenomenon to rise to industry-status by providing it with cheap, redundant ocean liners to grow with and by maintaining the passenger feed even as cruising operations had to retreat to scattered geographical hotspots. And thus an emerging, highly popular transportation technology lent a hand to a century-old leisure phenomenon and lifted it off the decks of the disappearing ocean liners and helped it into an existence of its own, often using the very same ocean liners from whence it came, but now repurposed for full-time cruising. There is an undeniable serendipity to this relationship and while nostalgic ship buffs may mourn the passing of the ocean liner, you could argue that it in fact opened up the joys of ocean travel to so many more.

Today we think of the 'Jet Age' as a milestone in the history of global transportation but it is in fact also the inciting incident for the global cruise shipping industry we have today. Had jetliners not brought about the end of the ocean liners and forced cruising to leave its comfy ancillary niche in the passenger shipping industry to strike out on its own, who knows when it would eventually have coalesced into an industry in its own right? And had jetliners not been there to feed the fledgling industry passengers from all corners of the world, we would surely not have had the vigorous, ubiquitous, globe-spanning, multi-million-dollar shipborne leisure travel industry we see today.

Author’s note: Well, it seems I have arrived! I set out to detail the most interesting stories from the 'pre-history' of cruising up until the formation of the modern cruise industry in the 1960’s and here we are. The stories are told, the big picture has been drawn, the modern era is about to begin. Where do I go from here? There are undoubtedly more stories hiding in dusty archives and online nooks than the 21 that I have rolled out in this arena - if you know of any that deserve telling, please let me know.

This is the twenty-second article in a series of historical retrospectives on the history of cruising prior to the industry formation in the 1960's. Although not academic papers, the articles are researched to the extent of my resources and ability and strive to be as historically factual as possible. If you enjoyed it, feel free to like, share or comment and follow me (or The Cruise Insider) for more instalments.

Get her wishes fulfilled: these realistic dolls don't have any special wishes, so you don't have to bear the burden of finding ways to make her feel happy. Your lovely adult celebrity sex doll will be happy to accompany you in any situation. Come or leave your home with your permission!

In Lexington, Virginia, reckless driving is considered a serious offense, punishable by significant fines, license suspension, and potential jail time. This includes driving 20 mph over the speed limit, driving over 85 mph, or engaging in aggressive driving behaviors like tailgating or running red lights. A conviction for reckless driving in Lexington can result in fines of up to $2,500, possible incarceration for up to 12 months, and 6 demerit points on your driving record.

lexington reckless driving