Early Caribbean II

- Jacob Lyngsøe

- Jun 5, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Jul 28, 2025

Part II: Rise of a Region

In early 1893 wealthy American entrepreneur Henry B. Plant dipped his toe in the previously untapped leisure travel potential of the Caribbean region by sending the unassuming passenger steamer SS Halifax of the Plant Line on a series of three experimental leisure cruises out of Tampa, FL, calling in Kingston, Jamaica and in Nassau, Bahamas. That is an event that you might have just finished reading about in Part I of this tale (if not, you should!) and is - by my research - likely the first designated commercial cruise undertaken in the Caribbean. Nothing more came of this experiment (though alledgedly more for political than for practical or commercial reasons) but across the vast Atlantic Ocean others were eyeing that same leisure travel potential with interest and preparing to follow in Plant's wake soon ... real soon, in fact.

Orient Steam Navigation Company

The first ‘true’ advertised leisure sailing out of Europe, bound for the Caribbean that I have been able to trace is likely this one in 1893 (only months after Plant’s experiment); On 22 November 1893 the British Orient Steam Navigation Co. sent one of their passenger ships, the SS Garonne, on a designated autumn cruise of the Caribbean. It was an expansive 66-day cruise out of London/Tilbury that took in Madeira, Tenerife, Barbados, Trinidad, Grenada, St Lucia, Martinique, St Kitt’s, Santa Cruz, Jamaica, Cuba, Nassau, St. Michael’s and Lisbon. This feels corroborated by the fact that Orient Steam Navigation Co. was indeed a first mover on commercial cruising among the major European shipping companies and did indeed dedicate two of its passenger steamships, the sisters Garonne and Chimborazo, to semiannual leisure cruising during the slack summer season of their regular UK – Australia route. Their first true leisure cruise went to the Mediterranean in 1889 so it feels quite plausible that by 1893 they felt ready to take on the Caribbean. To appreciate how small the cruise market was back then, bear in mind that in the latter half of the 1880’s less than 20 leisure sailings were apparently carried out (all British – the Germans had barely even clued on to the concept yet) so it’s not like there was a myriad of players or offers out there.

The SS Garonne

The Garonne was a single-screw barque-rigged passenger steamship from 1871, weighing in at 3,876 GRT and with a length of 116,5 m / 382.1 ft and breadth of 12,5 m / 41.4 ft. That made her about twice as big as the Halifax, yet only about the size of a modern-day expedition cruise ship / yacht or (if you are more of a sports enthusiast) slightly longer than a standard soccer field and slightly wider than a doubles tennis court. The Orient Line was renowned for the quality, comfort and luxury of their ships and the Garonne was indeed all of that, plus fitted with electric lights and featured ‘.. [ample] bath, closet, and other sanitary provisions.. throughout the ship, .. all easily accessible, yet all.. secluded, and in every respect perfect’. Assume what you will about ‘perfect’ sanitary provisions of the late 19th century but they were all communal, in case you didn’t get the hint about ‘seclusion’. Apart from the Saloon Deck plan below, I don't have much other information about the features / layout of the ship, but going by standards of smiliar ships, I would assume she likely also featured a Drawing Room / Library, a Smoking Room or a Ladies Salon on the promenade deck. Given that second class was likely unoccupied on the cruise, the second class dining saloon may well have doubled as a Social Hall also.

Your Cruising Experience

The meals would have been the fixtures of the daily schedule, likely three square ones plus one tea time, and they would have been quite varied and enjoyable - even to a modern-day cruiser. By the late 1880's 'refrigeration apparatus' was common on long-distance vessels, allowing for fruits, meats and vegetables to keep much longer and for meals to be quite balanced and refined, even during long stretches at sea. Religious services on Sundays / holidays would have been another cornerstone on the schedule, likely conducted by the captain or a senior officer, unless a willing man of the cloth happened to be onboard. Other social events or leisure activities were organized by the ‘Amusement Committees’ (usually consisting of chipper, extrovert fellow guests volunteering rather than company cruise staff) who would use the ships notice board to advertise deck game tournaments, sports activities, guest talent shows, musical performances (there were musicians onboard, if not an actual band) and what have you.

The Price of Leisure

I do not know for sure how much such a leisure odyssey would have cost. Sources suggest that the standard day rate for shorter European cruises was about £1 per day - equivalent in purchasing power to about £164 in the 2020’s – I do not know if that holds true of longer voyages but if it does, that would put the cost of the 66-day cruise close to £11.000 in today’s money. Let’s just safely assume it was for the very wealthy only and therefore occupancy probably did not exceed the first-class capacity of 72 berths, unless it was also possible to purchase passage between ports in second (92 berths) or third class (265 berths) .. though I doubt that. If anything the second class cabins were more likely to have been taken by personal servants or valets, accompanying their masters on the adventure.

Passing the Sea Days

It would have been a long, slow journey - the Garonne sailed at a cruising speed of 12 knots and at that speed the first leg from England to Madeira takes five full days (best case scenario). Of course, once they arrived in the Caribbean the pace would have quickened as all the ports were spaced fairly close together, but still you had quite a lot of sea days to fill. Luckily Orient Line was no stranger to lengthy sea voyages – the liner journey Downunder took between 30 to 60 days in itself – so they had plenty experience keeping guests comfy and cheerful at sea. A Bible-sized Orient guide book produced by the company for general distribution on their ships (a sort of guest manual of lengthy sea travel) suggested you relax in a deck chair, engage in some reading, sketching foreign landscapes and horizons from the deck or partaking in some of the activities of the Amusement Committee.

Contemplation and Cocaine

To the modern generations that have forgotten the art of relaxing without artificial visual or audio stimuli and who barely know how to talk to strangers without a digital interface, this may sound unbearably dull and unappealing, but I can dig it. That is of course a modern viewpoint that I as a 21st century native get to apply – Victorian-era travelers would not have known any other way to travel or experience – but just imagine for a second leaving behind not just your everyday hamster wheel of existence, but the digital one as well, removing yourself from all news and stimuli of the world for days and weeks on end, engrossing yourself in simple yet creative and contemplative pastimes for hours, engaging in friendly and spirited games, meals or discourse with your fellow (offline) passengers who probably share not just your station in life, but also your passion for travel and discovery, deeply appreciating travel experiences and scenery you were not yet too jaded or too focused on Instagramming to enjoy. Honestly, I could see a daring new cruise line pitch for an IRL-type cruise to a market segment increasingly jaded and weary from too much digital existentialism. And even if I am wrong and the sedate 19th century pace of life has me crawling on the walls within days, I can just pop some Lorimer’s Cocaine Lozenges to take my mind off it. No, I kid you not – on page 6 of the 1888 Orient Line Guide Book is an ad for Lorimer’s Cocaine Lozenges, ostensibly as a cure for sea sickness, but 'probably good for ... every other form of sickness’ as the ad cockily declares.

Coming of Age

The prolific cruising activities of the Orient Line in the late 1880’s and early 1890’s marked the ‘coming of age’ of the commercial cruise phenomenon in Europe, developing it from occasional fringe operations to a full-time commercial cruise market, spreading its area of operations across the Atlantic and giving it the popular appeal it has cruised on ever since. It’s pretty remarkable that the Caribbean entered the destination portfolio this soon, despite being close to 4000 nautical miles away from England and relatively obscure in the public mind, but such was the powerful draw of exotic leisure cruising, at least for those that could afford it. The West Indies (as the Caribbean was called back then) would remain a recurring destination in the annual cruise programs of Orient Line but it would be a while before any competing European shipping company tried to copy the success.

There would soon be North American competition though..

The Quebec Steamship Company

In 1894 the Canadian Quebec Steamship Co. began operating ‘winter cruises’ from New York to the West Indies every January and February. With British travel agents Thomas Cook & Sons as passenger agents, Quebec Steamship Co had already pioneered leisure travel to Bermuda in the 1880’s – I hesitate to call these sailings cruises only because a round-trip with only one port of call really seems more akin to an ocean passage / ferry service, but they supposedly had a leisure vibe to them. By the way, if you are wondering why it’s yet another Canadian company taking the lead on the development of the Caribbean as a cruise destination, there is a reason for that… and it’s seasonal. Most Canadian waterways and coastal areas froze up in winter to a degree that not even iron hulls and steam engines could deal with it (coincidentally also the reason why the Quebec steamships operated from New York and not from inland Quebec in winter). Canadian merchant ships needed to pursue business where they could find it in winter, be it cargo, line passengers or – increasingly – leisure travelers in desirable regions and seasons. So that’s how Canadians became involved in cruising adventures thousands of nautical miles from Canadian waters.

Escape from Winter

This also provides a direct parallel to a major appeal of these first cruises; that being escape from the harsh North American winters. If you find yourself wondering why escape from bad winter weather held such a powerful appeal for North Americans and yet was seemingly absent from contemporary British marketing (even though Britain is practically infamous for its crummy weather) - well, that's the difference between maritime and continental climates. Despite the fact that all of Great Britain sits squarely above the US-Canada border on a latitudinal axis, British winters are - through various quirks of oceanography and meteorology - actually a lot milder than many North American states and not top of the list for wanting to get away from it all (though almost certainly still on the Top Five). But for those gilded age family dynasties - many of whom lived in exactly those Northern states who took the brunt of the fierce continental winters - escaping winter was a major motivation to seek out leisure travel in Southern latitudes.

A Romantic Appeal

But a more important appeal than lovely weather for North Americans were the individualistic and impassioned sensibilities and priorities brought on by the new cultural and intellectual movement of Romanticism. Not just as in the reverence for and attraction to untamed and exotic nature that we touched upon in Jamaica but also as an idealization of the past as a nobler time and as a celebration of the 'sublime' (a philosophy term denoting the greatness.. nay, awesomeness of nature and the world around us). And where better to find beautiful and exotic nature mixed with easily romanticizable colonial history than on the Caribbean frontier? This was very different from the early pitch of European cruising which was largely based on the emulation of the (educational) 'Grand Tour' and the famous sights of European antiquity and renaissance for appeal. The Caribbean islands held no such grand historical or cultural legacy to explore and the ruins of the great mesoamerican civilizations on the mainland had barely even been excavated yet but it could sweep you off your feet with its 'sublime' nature, colonial charm and the allure of 'untrodden ground' - going where others had not gone before in an act of self-actualization. I am already way out of my philosophical depth here so let's just simplify it and say that the Caribbean held more of an emotional appeal, as opposed to the more intellectual appeal of Classical Europe, and that was what powered the leisure movement to the region.

The SS Madiana

First ship heading south in 1894 was the 2.948 GRT SS Madiana – a 19-year-old single-screw iron cargo liner some 105,1 m / 344.8 ft long with a 12 m / 39.4 ft beam – so slightly smaller than the Garonne. She had spent most of her existence as the SS Balmoral Castle for Castle Mail Steam Packets Co. and though not a spring chicken, she had received an extensive refurbish when she was bought by Quebec Steamship Co. in 1892, so she would have appeared relatively ‘new’ and up to the task. I have not been able to find a deck plan for her but going by descriptions in an 1895 travel brochure, she featured a spacious and elegant Main Saloon, a Social Hall and a very attractive Smoking Room on the upper deck. The cabins were likewise well appointed and spacious – 8 feet square by 8 feet high – and were ventilated, electrically lit and featured stowable wash-bowls for personal hygiene. What I have not been able to find any information on is her passenger carrying capacity and the breakdown by class but given that she was smaller than the Garonne and featured notably larger cabins, it likely wasn’t even as much as her.

A Different Crowd

Even though the Madiana was only four years younger than the Garonne, outwardly they seemed to represent two different ages of ocean shipping; the stylish clipper bow and swept lines, the triple square-rigged masts and the flush decks of the Garonne very much made her look like one of the sailing ships of old, whereas the Madiana with her no-nonsense straight-stem bow, simple twin pole masts and budding midship super-structure looked more industrial and contemporary (although the whirlwind evolution of late 19th century ship design and technology made ‘contemporary’ a very transient term). Appearances aside, the cruise experience likely felt much the same as onboard the Garonne – in terms of era, standards of creature comforts and levels of technology the two ships were clearly cut from the same cloth. Where you might have felt a difference in experience would have been with your fellow guests – this was one of the first times North Americans appeared by the boatloads on leisure cruises and they would surely have brought along a much different culture from the British. Don’t worry, I’m not going to deep-dive into a study of national cultures but just imagine for a moment the ‘social vibe’ of a ship loaded with a bunch of brash, progressive, self-made Evangelical republicans vs. one loaded with a bunch of highly-mannered, conservative Anglican monarchists. I don’t have first-hand accounts or cultural observations from back then but it stands to reason they would have carried themselves differently, enjoyed themselves differently and experienced the world differently. Hmm, maybe that’s a subject for a later story - I'll put a pin in it!

Series of photos from a Madiana Cruise, Charles W Blackburne,

Gift of John Noll in honor of Richard Waldman, 2013 Int' Center for Photography

The Itineraries

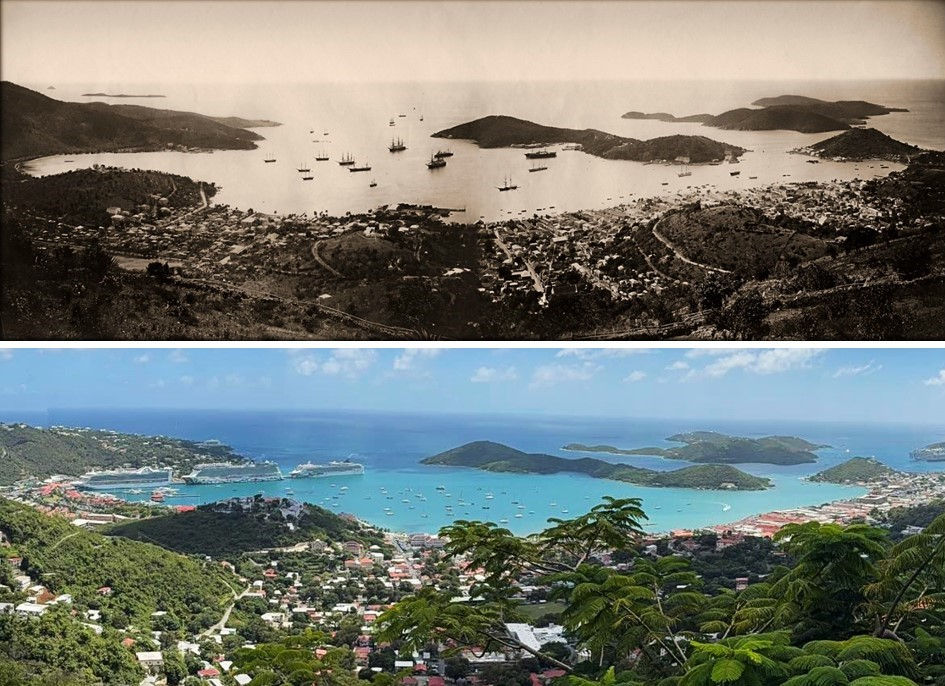

The voyages were fairly identical with only minor variations – a southbound beeline from New York to the Leeward Islands (sometimes stopping in Bermuda) and then meandering down through the Leeward and Windward Islands until South America before doubling back to New York, sometimes by way of Kingston, Jamaica. Cruise duration was typically around 30 days, starting and ending with the five-day sail from/to New York across the Atlantic, but otherwise hitting a new port every day and only cruising between ports at night. Destinations would typically include ports like St Thomas, St Croix, St Kitts, Antigua and Guadeloupe in the Leeward Islands and Dominica, Martinique, St Lucia, Barbados and St Vincent in the Windward Islands as well as Demerara (British Guiana and now present-day Guyana), Jamaica and Bermuda (starting in 1895). The fares for this exclusive adventure ranged between $130 – 200 per person (the equivalent of $4,884 - 7,514 in today’s purchasing power) and included all onboard accommodation and meals but not beverages, shore excursions or other shoreside expenses. Excursions ashore are mentioned in brochures but not in a formalized way with a set program. It merely states that excursion arrangements can be made by cabling ahead and tasking ships’ agents with setting it up for guests – the costs of which then later to be settled with the purser – so mostly as a passenger courtesy rather than a business opportunity.

Initial Success

The first Caribbean winter season for the Canadian Quebec Steamship Co. must have been a success, because in the 1894-95 winter season the Madiana was joined by two more Quebec Steamship Company ships - the Orinoco (1881) and the Caribbee (1878). Both ships were similar single-screw cargo liners in the 1.800-2.000 GRT weight range, both slightly younger and slightly smaller than the Madiana but neither seems to have made a significant dent in maritime history… apart from the dent the Orinoco left on the SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse when she collided with it in Cherbourg in 1906. Besides that, I have not been able to find much of any information or photos on either ship, but that’s okay. We don’t actually need to detail the inrush any further - the point is already made; Caribbean cruising had now become a regular and fairly popular recurring activity that would only increase in volume and frequency from now on. American, British and Canadian ships had already carried leisure travel into the Caribbean and by January 1896 the Germans joined the party with Hamburg-America Line’s Columbia cruising to the West Indies and the Spanish Main from New York. With that all the world’s cruising nations were plying the Caribbean Sea and it would only grow from there.

Cruising for Health

One final thing helped launch the Caribbean as a most popular cruise region; the medical stamp of approval. In 1897 British medical professional E. Hart undertook a Caribbean cruise on the Lusitania of Orient Steam Navigation Company and praised the curative and convalescent effects of a sea voyage in a brief article ‘The West Indies As A Health Resort. Medical Notes Of A Short Cruise Among The Islands’ published in the highly esteemed British Medical Journal;

Surely such hours of unalloyed enjoyment, of genial warmth and sea breezes, are more agreeable, and often not less efficacious, prescriptions to the sick and convalescent than a thousand pills and potions.

Page 658, Sept 11, 1897

This could have been easily dismissed as just another medical recommendation in the vein of ‘Eat healthy’ or ‘Exercise more’, were it not for the fact that it fed right into the growing fascination with maritime leisure travel. In a time when social and leisure activities were highly ‘functional’ (meaning you did something for the outcome of it, not for sheer enjoyment of it) and lengthy vacations were still a novel phenomenon, it lent a purpose to a travelling public that perhaps still felt a little stigmatized admitting that they were 'just going out there for fun’.

The Caribbean Cruise Adventure

The Great Caribbean Cruise Adventure as we know it today came about through a confluence of a few different things; A number of Caribbean colonies and nation states actively looking for profitable additions to their one-trick economies and North American shipping companies actively looking for new business areas when their home waters froze shut. The Romantic movement had inspired the pursuit of individual and passionate experiences, a reverence for nature and bucolic scenery and a glamorization of ‘untrodden ground’ that fueled the leisure travel revolution and a new North American elite riding high on the Gilded Age looking for somewhere pleasant and interesting to spend the harsh North American winter in comfort and pleasure. This all happened in a relatively brief time window from early-to-mid-1890’s with ships of leisure arriving from both North America and Europe. And just like that the Caribbean had suddenly become a popular cruise destination – a novel one and a rather exclusive one, but a popular one none the less. Modern mass media would help spread the word, technological ship evolution would enhance the experience and multiply the number of guests many times over and a local tourism economy would emerge across the islands. But the adventure had truly begun in those last few years of the 19th century.

The Real Story?

So is this the definitive story of how ‘real’ cruising in the Caribbean started? Were these really the true players, events, sailings and ships that pioneered the Tropical Frontier? Honestly, I don’t know - this is a very uncharted area of cruise history in as far as not much official record-keeping of early leisure travel took place and what little did take place is perhaps not immediately available to me from half a world away. These are the scattered facts that emerge when I stirred the great big digital cauldron that is the internet (and quite a few books too) and this is the tale I wove of it. I am not ruling out there isn’t other physical evidence out there, in local museums, personal collections or dusty archives (that has never transitioned online), that can tell a more nuanced or perhaps completely different story. So take this as a story, though not necessarily the full story of how the Caribbean cruise adventure started.

This is the twenty-seventh article in a series of historical retrospectives on the history of cruising prior to the industry formation in the 1960's. Although not academic papers, the articles are researched to the extent of my resources and ability and strive to be as historically factual as possible. If you enjoyed it, feel free to like, share or comment and follow me (or The Cruise Insider) for more instalments.

Comments