The Lost Origin

- Jacob Lyngsøe

- May 12, 2020

- 14 min read

Updated: Jun 7, 2025

How old is cruising as a leisure travel product? – When did the first paying guests venture out to sea for no other reason than the pursuit of leisure and exploration?’

That is a question I frequently start out with when ‘talking cruise’. Many laymen answer ‘In the sixties’ which would be true if I had asked about the origins of the modern cruise industry, but to find the genesis of cruising as a commercial leisure travel phenomenon, you need to go further back … much further back.

INTERESTING and CLASSIC EXCURSION Steam to Constantinople, calling at Gibraltar, Malta, Athens, Syria,

Smyrna, Mytilene and the Dardenelles

These were the words that heralded a new vacation experience in the London Times on 14. March 1843. And it stirred enough interest in early Victorian England for Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company (today's P&O) to go ahead with their plan to designate a late summer 1843 sailing of the paddle steamer Tagus as the first official pleasure cruise in history. So take a moment to contemplate that cruising as a commercial leisure travel phenomenon is actually more than 180 years old today.

Riding the Lines

At this time individual travellers and groups under travel agent lead had already successfully used the Royal Mail Steamer network (instituted in 1840) to go exploring and sightseeing by ship, although this usually involved transferring between different ships for each leg of the journey and staying one or more nights ashore at popular destinations between transfers. Thusly this did not really qualify as a continuous cruise and was more akin to maritime 'interrailing' on the regular mail steamer network. However, this sailing seems to have been the first time a mail steamer departure was advertised with the joint purpose of mail service and leisure/sightseeing for paying passengers. P&O had just opened up a new monthly service to the Levant (the countries at the far Eastern shores of the Mediterranean) and likely saw the addition of a 'cruising angle' as a promising way to drive more passenger volume toward the new route since public interest in leisure travel was on the rise.

The First Sailing

With a 1927 reprint of an 1843 travel account from the Illustrated London News as my only source (helpfully provided by the P&O Heritage Collection), I can provide a bit more detail on the cruise itself, though many details still remain sketchy or uncorroborated. The Tagus set out from Southampton - P&O's home port - on Tuesday the 15th of August 1843. The travel account suggest she may only have carried 12 guests on this first 'cruise', though whether that refers to total number of pax onboard or only to those out for leisure travel is not known - either way it was well below her max occupancy of 86 pax. In chronological order, the Tagus called at Gibraltar on August 21, Malta on August 26, Piraeus, Greece on August 30, Smyrna (present-day Izimir, Turkey) on September 2 and its final destination, Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey) on September 5 - the advertised calls in Syria and Mytilene (Lesbos) seem to have been omitted from the final itinerary (they certainly are from the travel account) and the Dardanelles refers to the Strait of Çanakkale (Gallipoli), so that likely refers to scenic cruising rather than an actual port of call.

All in all it was a 22-day voyage to Constantinople with 5 port calls. The travel account fades out in Constantinople - the official final destination - and it is not clear whether the author returned to Britain on the Tagus (likely by reversing the outbound itinerary) or chose to stay for sightseeing and catch another mail steamer back, perhaps the Braganza which alternated with the Tagus on the same itinerary on a monthly basis. Whatever the case, it is apparent that - factoring in the return journey - you would have had to set aside the better part of two months to go on an adventure like this. Regrettably the travel account contains no specific information on the cost of such an adventure, other than describing it in passing as a 'moderate outlay' (which would mean more if we knew the financial and social circumstances of the author), but it is fair to surmise that it would have been accessible only to the wealthy and privileged of the age.

Dawn of Mass Tourism

The 1840's were the dawn of mass tourism in the United Kingdom. An emerging British middle class was slowly gaining the means and time to go on holiday and a growing network of mechanized mass transit systems, i.e. trains and steam ships, was taking people further than they had ever gone before. It is no coincidence that this was the decade when Thomas Cook launched his mainstream travel agency and started offering some of the first commercial holiday package tours. However, the cost of a two-month, all-inclusive cruise would very likely have been out of reach to any of Thomas Cook's customers. Such a caliber of leisure travel was almost exclusively frequented by aristocrats, noblemen, landed gentry, famous artists and the newly made plutocrats of the Industrial Age. And I suspect what was driving them was not just mere wanderlust or idle curiosity, but likely an almost 200-year-old custom; the Grand Tour.

The Grand Movement

Ever since the late 1600's an educational trip through Classical Europe - a Grand Tour - had been a well-established rite of passage for young European men of sufficient means and rank once they came of age. It was meant to familiarize the next generation of high society denizens with the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to introduce them to the aristocratic and fashionable society of the European continent. Such trips could take months or even years depending on your educational discipline and travel budget but was considered essential in the grooming of an educated and worldly gentleman. By the 1840's the custom was waning in high society but after more than a century of being de rigeur for any aspiring upper class socialite, it still held considerable selling power, especially for those on the middle rungs of the social ladder who sought to emulate their betters. This new format of leisure travel held the promise of doing much the same as a Grand Tour (and P&O practically promised as much by using the phrase in their advertising), but at a lower investment in time and money. After all, much of Classical Europe was located on or near the coast, so a Mediterranean cruise would enable travellers to tick most of the boxes of a traditional Grand Tour (though without as much depth or immersion). So it was a convenient way for social climbers to boost their status, to enable them to keep up their end of a learned conversation about the culture and history of Europe or - at the very least - to be able to say 'Oh yes, Florence! I've been there! Lovely place!'

But while the cruise product was aimed squarely at the wealthy and upper class, the actual experience would have been a far cry from today’s luxury cruise experiences. Now, the author of the travel account is unfortunately too busy describing the destinations to go into any detail about the onboard experience, but I know enough about maritime affairs of the age to be able to extrapolate to some extent what on board life on this first cruise could have been like. So come aboard with me as I paint a picture of what you would have been in for as a cruise guest on the Tagus.

For detailed specs on the Tagus visit the P&O Heritage ship archive here.

Welcome Onboard

At 55,5 m / 182 ft length and a beam of 8 m / 26 ft. the 909 GRT Tagus was only slightly longer than two tennis courts, laid end to end, and only narrowly the width of one court across. She was seven years old at the time of the cruise, barely a third of the way through her commercial lifespan, but plenty old to show the wear of every ocean crossing. She was built as a long-range auxiliary paddle steamer, meaning she had steam engines and paddle wheels as well as the masts and rigging of a sailing ship, enabling her to switch between the two means of propulsion to keep to schedule (or - as was often the case - resort to wind power when her steam engines broke down). As a mail steamer she was built for speed and endurance – to deliver mail, cargo and travelers to the far-flung reaches of the Empire as fast as possible. Bear in mind, 'speed' in this case means no more than 9.5 knots (17,5 kmh / 10.9 mph) which was her maximum cruising speed - meaning it would take her the better part of 6 days just to get from Southampton to Gibraltar in ideal conditions.

I have not been able to dig up any deck plans for the Tagus but I did manage to find the one above for Cunard’s RMS Britannia, likewise built in Greenock, Scotland three years after the Tagus (1840) – both ships are of a similar three-masted, wooden paddle steamer design with two-cylinder side lever steam engines (though the Britannia is slightly larger) so it’s fair to surmise that the designs would have been very similar. You can see the passenger saloon on main deck aft and the passenger accommodations on the deck below and the Tagus would very likely have had a similar configuration.

The Tagus carried a crew of 36 and her passenger capacity was around 86 at maximum occupancy but the comfort and enjoyment of said passengers would absolutely have been a secondary consideration to her main purpose – as would have been apparent from the cabins already. Your ‘stateroom’ would have been a dim and damp rectangular wooden box, likely no more than 6 sq.m. / 60 sq.ft., lit by flickering oil lamps. Furnishings would have been sparse and basic; bunk beds, washstand, closet, seat and little else. Forget about a balcony – at best you would have had a small, sealed porthole, offering no ventilation and probably very little view due to grime and algae. No electricity (as this would not be introduced on ships until 1880) and no in-cabin toilet or bathroom either – there’d likely be a communal latrine along the corridor or maybe just a board with a hole in it, suspended over a gutter or even the open ocean. There would also be at least one bathroom where you would be able to wash down with salt water, but you would have to schedule a time with the steward to use it. Devoid of any air-conditioning, the room would have been freezing cold or stiflingly hot, depending on the region and season (and bear in mind August is the hottest month in the Mediterranean), and the air stale and damp with a strong fishy odor from the whale oil used in the lamp (unless you were lucky enough to have one of those newfangled lard oil lamps that did not produce much odor).

Food & Beverage

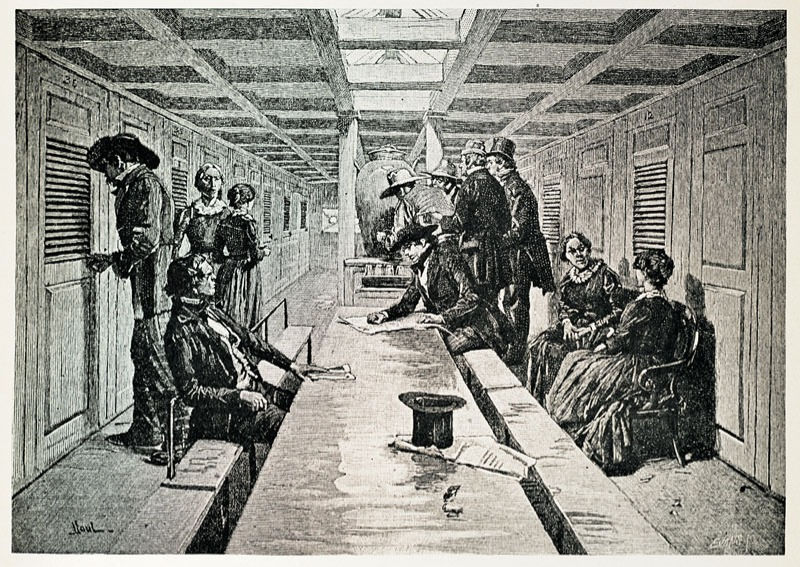

In terms of public spaces, there’d be only one: the ‘dining room’ or 'saloon', located aft in the passenger section. Lit by oil lamps, windows or overhead skylights, the long room would have featured a long wooden table with bench seating where passengers would have taken their meals and congregated when not out on deck or in their cabin. The meals would have varied in freshness and diversity, depending on when the ship was last able to take on fresh supplies. With no refrigeration on board, fresh produce, meats and dairy have a limited shelf-life, especially in warm Mediterranean climates. To enrich the onboard diet, many long-distance liners would carry livestock onboard, like cows for milk, chickens for eggs or pigs for meat, on the longer legs of the journey. Whether this was practised on the Tagus I do not know, but either way, with up to 100 mouths to feed (incl. crew) supplies were always stretched thin and preserved foods most likely made up the bulk of the onboard diet. On the plus side wines and spirits kept quite well on board and were - up until the 1870’s - part of the complimentary provisions, so if you didn’t care for the food, you could always substitute with a stiff drink which many did … all day long.

An Experience for the Senses

Once underway, the din of the steam engine and the splashing and creaking of the paddle wheels and hull would have been constant, except when at anchor/docked. Add to that the clanging of the blacksmith's hammer from his workshop, the half-hourly ringing of the ships bell to aid watchkeeping and the (potential) crowing, bellowing and grunting of various livestock kept onboard. For those prone to motion sickness every moment at sea would have been insufferable, as the small vessel would have been very susceptible to wind and waves. The smells would not have helped – the ocean breeze on deck may have been delightful, but below decks you would be met by a barrage of smells; from the galley, from the latrines, from the engine room etc. A melange of tar, creosote, oakum, bilge water, kerosene, oil, coal and more would have exuded from the hull and mixed in with all the smells of human activity on board, including the body odors of your fellow passengers who may or may not have had an opportunity to schedule a bath with the steward recently.

Oh, and did I mention the sturdy rat population, that a ship of this size and age would invariably have had? But if you were lucky there would be one or two ship's cats onboard to keep the rodent population under control. Infestations and disease were commonplace on passenger ships of the 1840’s, partly due to the unsanitary conditions described above and partly because no government started legislating on maritime hygiene of passenger-carrying vessels until the late 1840’s, so it was basically up to the operating company to decide what onboard standards for hygiene and sanitation should apply.

Out On Deck

Out on deck would have been the place to be, but space was at a premium. Between masts and rigging, two massive 7 m / 24 ft diameter paddle wheels, funnel, bridge (so called because it 'bridged' the two massive paddle wheel casings), lifeboats and miscellaneous machinery, little space would have been available to the passengers. Since suntans were still considered marks of peasantry in Victorian England, no one was eager to expose themselves to the sun and would likely have sought shelter from the sun under a large awning somewhere aft. On deck would also have been the only place you were allowed to smoke, if you were so inclined, as all smoking below deck was banned for fire safety reasons. Those that went for promenades would have done so with hats or umbrellas and with multi-layered, heavily pleated Victorian suits and dresses (as was the fashion) providing ample protection from the sun, though perhaps little comfort in the heat. The real downside to the deck was the copious amounts of smoke and coal dust that would descend from the smoke stacks whenever the wind lulled or changed direction.

Pastimes and Shore Times

On board entertainment would have consisted of whatever books or creative pastime you could pack or whatever talent you and your fellow passengers brought to the party. In Victorian times game play, musical performances and talent shows quickly became the preferred sociable way of staving off boredom on long voyages and it was not unusual for the more extrovert, attention-loving passengers to practically take on the role of ‘cruise director’, whether invited to or not. And if you could entertain your fellow passengers with a musical, thespian or other artistic talent, you would have been in high demand for some surprisingly entertaining and jovial soirees in the dining room (fuelled by the free booze policy). There would have been no activity program (save for perhaps Mass and meal times) and no cruise staff to provide diversions, and given rigid Victorian class divisions it’s unlikely the passengers would even have socialised with crew, save for the Captain and highest-ranking officers (about 4-5 people out of the crew of 36).

As for port calls, I admittedly know very little about how these played out, except to speculate that the calls would probably have been longer than the standard half day / full day routine of today’s cruise ships. Partly because the process of servicing and supplying a steam ship would have taken longer and partly because passengers would have needed more time to visit the local sights, with only horse and carriage transportation at their disposal. Quite a few of the destination ports did not have sufficient docking space for ships, so more often than not, going ashore involved a precarious descent via rope ladder and a tender ride ashore by row boat. Sightseeing in port was obviously a popular activity from the beginning, but it would likely have been ad hoc arrangements cobbled together on arrival with entrepreneurial locals that used the advertised steamer schedule as a guide to picking up sightseeing gigs. Organised Shore Excursion programs offered by the shipping company wouldn’t be a thing until decades later. While electrical telegraphs were in common use in the 1840’s, wireless telegraphy between ship and shore would not come along for another 50+ years, so any request for local services would have had to have been communicated days, if not weeks in advance of arrival in port.

The big Question

You’ll notice that I am not putting a whole lot of effort into romanticising the experience – that’s because it wasn’t particularly romantic. Granted, 19th century travellers would have had less refined sensibilities than today’s cruise guests, but even so – this was a basic, arduous and, not to mention, dangerous way to travel. Ocean-going steam ships had only entered widespread commercial use over the last decade and while they had improved crossing speeds and enabled regular liner scheduling, they were not much safer than their wind borne predecessors – a long sea journey was not necessarily something you returned from alive.

So why go then? Why embark on a leisure cruise that was by all accounts, more trial than pleasure? Well, therein lies the answer to why we have a global multi-billion dollar tourism industry that includes not only a booming cruise industry, but also a fledgling space tourism industry. Because humans want to discover and experience the world, as much of it as they can. They want to see what’s beyond the horizon and nowhere on Earth is the horizon more clearly defined and more beckoning than at sea. So consider this the first time that desire was given a convenient and dedicated format to occupy.

From this point on, ‘cruising’ was here to stay - it would take another 120 years and the demise of ocean liner shipping before it turned into an industry in its own right, but that’s an entirely different story. For now, let’s just congratulate cruising on its remarkable 180+ years since its origin and wish it many more to come.

And about Bill..

By the way, in order to further promote their new tourism service P&O also invited noted author and periodicalist William Makepeace Thackeray to take ‘a cruise’ with them for free in exchange for writing about the experience (you have likely never heard of him but in his own time he was as ‘big’ as Charles Dickens). In July of 1844 he set off from Southampton and used 3 different P&O steamers (the Lady Mary Wood, the Tagus and the Iberia) to carry him relay-style for a full loop of the Mediterranean and back to England. He seems to have enjoyed the trip but for whatever reason got cold feet about attaching his own name and reputation to the ensuing book Notes of a Journey from Cornhill to Grand Cairo which was published in 1846 under the pseudonym Michael Angelo Titmarsh. P&O likely did not end up minding the missed PR opportunity so much as he was not uniformly positive about the experience, complaining at length about incessant seasickness and unpleasant experiences in ports. But other parts of it were quite favorable and though not the ringing endorsement P&O had hoped for, it undoubtedly helped generate publicity around this new travel trend.

The books copyrights have now expired and you can find a pdf-copy online (Google book search). Like our unknown travel writer, old Bill does not write much about the onboard experience or the ships themselves, as that was clearly not the focus of his attention, but as a ‘time capsule’ of an early cruising experience it is an interesting and amusing read, if you can abstract from the quaint language, the unabashed racism and the colonial condescension.

This is the first article in a series of historical retrospectives on the history of cruising prior to the industry formation in the mid-1960's. Although not academic papers, the articles are researched to the extent of my resources and ability and strive to be as historically factual as possible. If you enjoyed it, feel free to like, share or comment and follow me (or The Cruise Insider) for more instalments.

Comments