Soviet Leisure II

- Jacob Lyngsøe

- Dec 11, 2020

- 15 min read

Updated: Jun 7, 2025

It was like American cruising but the buffets had a lot more borscht and cabbage in them. It was like American cruising but the bars had 30 kinds of Vodka instead of 30 kinds of Rum. It was like American cruising but the entertainment featured Cossack dancing and balalaikas instead of Las Vegas-style shows. It was like American cruising but with a lot more KGB. It was like American cruising, but it was a lot cheaper. It was like American cruising, but it was Soviet leisure. Yes, besides running a domestic cruise fleet behind the Iron Curtain, the Soviet Union also operated an international cruise fleet that gained quite a loyal following among Westerners and took up a very special place in the global cruise industry over three decades.

If the ‘II’ designation in the title did not already tip you off, then this would be your last chance to skip back and read Soviet Leisure, Part I as some of this article is building directly on what came before.

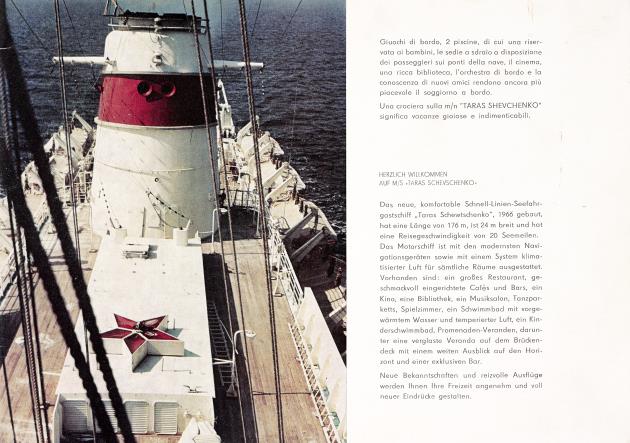

Once upon a time there were five poets …

No, really! That’s how this starts. In 1962 the Soviet Union commissioned a series of 5 original ocean liners from the East German shipyard VEB Mathias-Thesen Werft, all to be named after famous Soviet poets/authors. Starting with Ukranian poet Ivan Franko (who also lent its name to the class designation) they were Aleksandr Pushkin, Taras Shevchenko, Shota Rustaveli and Mikhail Lermontov. The five 19.861GRT passenger ships were 175,8m / 577ft long and 23,6m / 77ft wide, had 8 passenger decks and would accommodate (initially) 750 pax. They were the largest passenger ships commissioned by the Soviet Union but to truly grasp what made them unique, you have to consider the history of the Soviet merchant fleet.

In the early twentieth century the rivalling seafaring nations of Europe competed fiercely for commercial dominance of the Atlantic Ocean, if not in terms of who could cross it the fastest, then in terms of who could cross it the most luxuriously. That led to the construction of some of the world’s most iconic, beautiful and powerful ocean liners. But Russia (pre-1922) and the Soviet Union (post-1922) wanted no part of that game. With only far-flung ports like Leningrad (St. Petersburg), Murmansk and Odessa as viable gateways for Transatlantic travel they were not in any geographical position to compete on speed and the empire of workers and peasants did not have much demand for swift or luxurious sea travel. Construction of large and prestigious ocean liners was never prioritized and under Stalin, who lead the Soviet Union to peak isolationism after WWII, the Soviet merchant marine was generally neglected. But after Stalin died in 1953 First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev arrived in office with a new view of the Soviet Union’s place in the world.

Khrushchev wanted a large and modern merchant fleet that could a) safeguard the mercantile needs of the Soviet Union (as in handle all the cargo and traffic in and out of the Soviet Union by sea), b) help the Soviet Union earn and conserve foreign currency through international trade / shipping and c) function as contingency fleet for the Soviet Navy for overseas deployment (in other words, help prop up a global pro-Soviet empire of allies and puppet states). To put it in simpler terms; a fleet that could conserve, build and project the strength of the newly minted Superpower solely on Soviet terms. Throughout the 1950’s several shipbuilding programs ensued, mostly cargo vessels but also passenger ships, like the prodigious Mikhail Khalinin-class small liners that would later see frequent service as cruise ships, both domestically and internationally.

By the early 1960’s the Soviets decided to go big on ocean liners but the time of the big liners had already passed. The first commercial jet liner took flight in 1952 and if the 1950’s showed anything, it was that the future belonged to air travel and not to sea travel. Most of the other seafaring nations had stopped building large ocean liners at this point (except the Brits who built the Queen Elizabeth II in 1969 but had the great foresight to make her a perfect liner / cruise ship hybrid). Even considering that the Soviet Ministry of Merchant Marine did not operate on principles of market economy, it seemed an unusually short-sighted decision, but then again liner service was likely never the primary purpose of these ships. Seeing the growth in the Western cruise market, the Soviets likely (and correctly) assumed that the ships would make great steady sources of foreign currency if they could be chartered out internationally.

And finally, there was the military agenda; Ostensibly the powerful lifting gear and extra-large storage areas were there to allow guests to bring their cars along on liner passage … though why anyone would wish to export a Soviet car to the West or vice versa, was anyone’s guess. But by pure happenstance, this also enabled the ships to load and carry heavy military hardware. Likewise, the many bunk rooms with up to 6 pax capacity were ideal for accommodating budget class travelers, but could coincidentally also house a large number of soldiers (+ another 500 men could be carried on deck if needed). The enlarged storage and provision areas as well as the bigger fuel tanks and increased operational range (well over 10.000 nautical miles) were all ridiculously over the top for the needs of a transatlantic liner, but very well suited for a military supply ship carrying Soviet troops and hardware on long-range operations. True to Krushchev’s merchant fleet agenda these Poets could be turned into warriors (or at least military troop/supply ships) at short notice.

As the Ivan Franko-liners launched and became operational, they were assigned to different operators – the Ivan Franko (1964), the Taras Shevchenko (1967) and the Shota Rustaveli (1968) were assigned to the Black Sea Shipping Co. and registered in Odessa and the Aleksandr Pushkin (1965) and Mikhail Lermontov (1972) went to Baltic Sea Shipping Co. and registered in Leningrad (present-day St. Petersburg). The three Black Sea ships eventually never got to do much of the liner service they were built for – instead they settled into a routine of summers in the Black Sea, operating domestic cruises for Soviet citizens out of Odessa, and winters on the seven seas, doing international cruises under charter for Western operators. The two Baltic Sea ships were the only ones to do any liner service, specifically between Leningrad and Montreal, and outside of crossing season (April – September) they would do international cruises too.

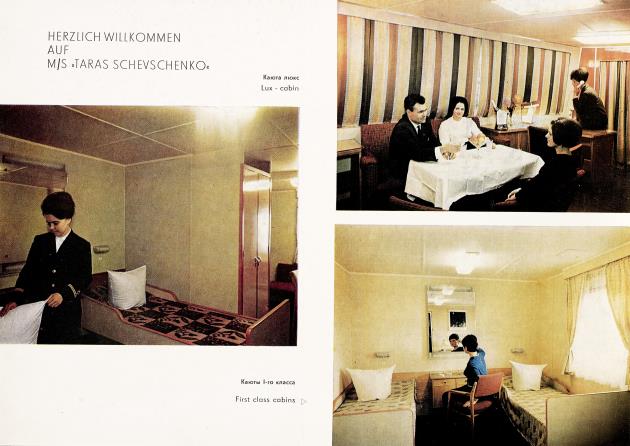

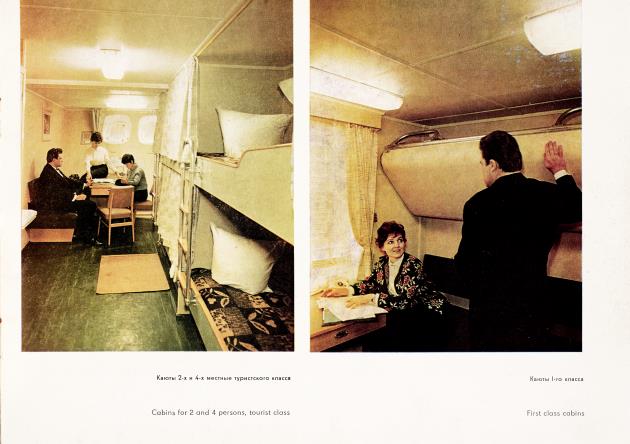

For a nation not exactly renowned for the aesthetics of their industrial hardware, the Soviet Union managed to produce some surprisingly beautiful ships; a raked bow with a hint of a curve, a well-balanced superstructure with stepped aft decks, stylish and well-proportioned radar mast and funnel and an elegant sheer emphasized by a white ribbon all around the ship. On the inside they were not too different in style or layout from their Western counterparts, though perhaps not quite as spacious or glamourous, but there was an odd mix of innovations and throwbacks. On the one hand all accommodation had sea views and the ship was fully airconditioned which was novel and progressive. On the other hand, only half the cabins had private facilities and the sanitary installations had 3 taps; hot, cold and seawater – a feature usually only found on pre-WWII ships. It seemed strange that ships that were so obviously built to show off Soviet ingenuity and engineering prowess to the West would fall curiously short of contemporary industry standards, but as mentioned above, perhaps there were other considerations at play.

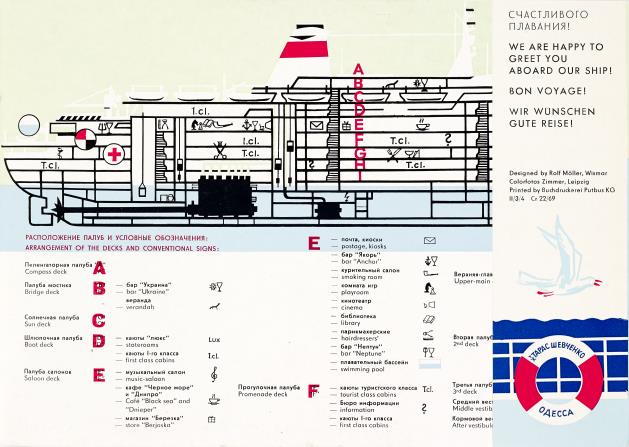

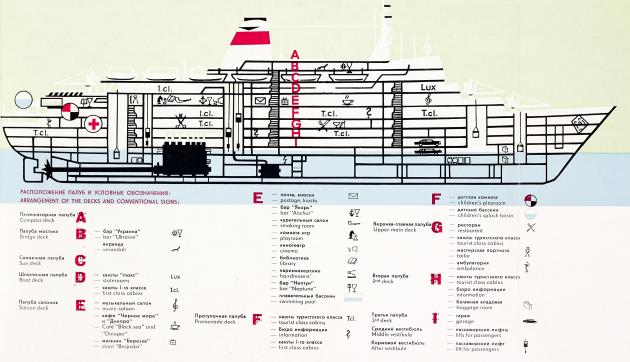

Cabin standards on the Aleksandr Pushkin, Fleetphotos.ru

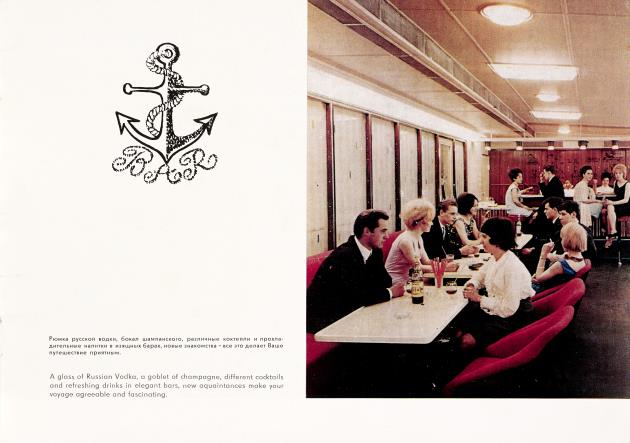

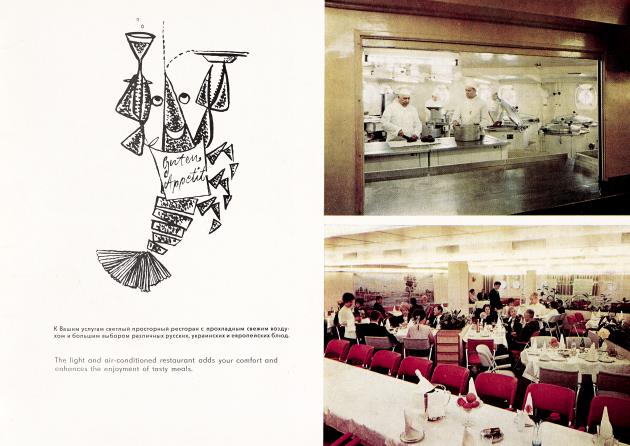

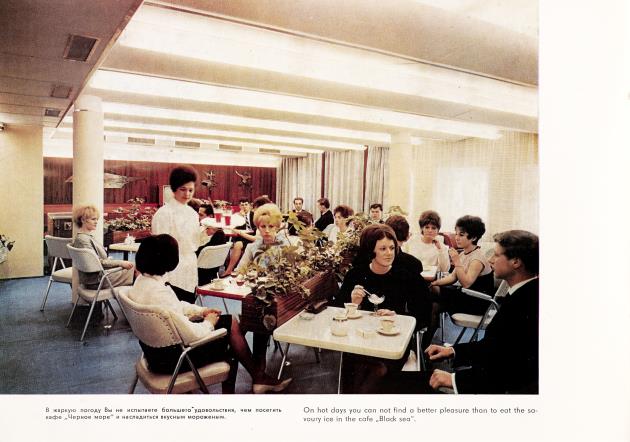

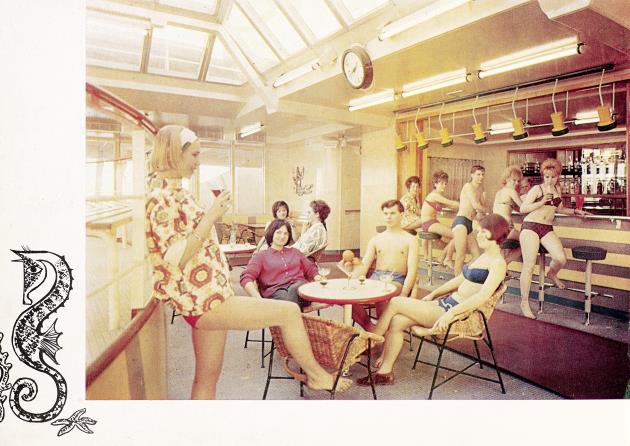

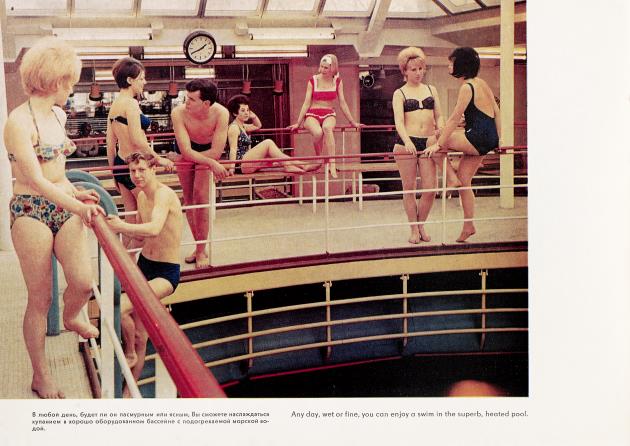

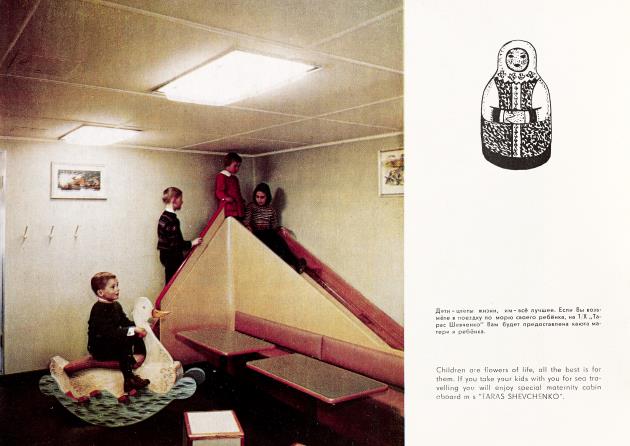

In the original configuration the ships accommodated 130 pax in first-class (2 or 4-berth cabins) and 620 in tourist-class (up to 6-berth cabins), served by a crew of 220. For public facilities they featured a main theater/lounge, a main dining room, several bars and lounges / cafes, a cinema, a library, a children’s playroom and a novel, glass-domed and heated swimming pool aft. Design refinements and alterations were introduced for each new ship as it became more and more obvious that none of them would ever operate the liner service they were intended for, so while Ivan Franko (1964) was recognizably an ocean liner at launch, the Mikhail Lermontov (1972) at her launch was recognizably more so a full-blooded cruise ship. Later refits would also see the sacrifice of all the cargo (military) space in favor of more cabin space but the initial layout of the ships was sound and practical enough to survive unchanged for decades.

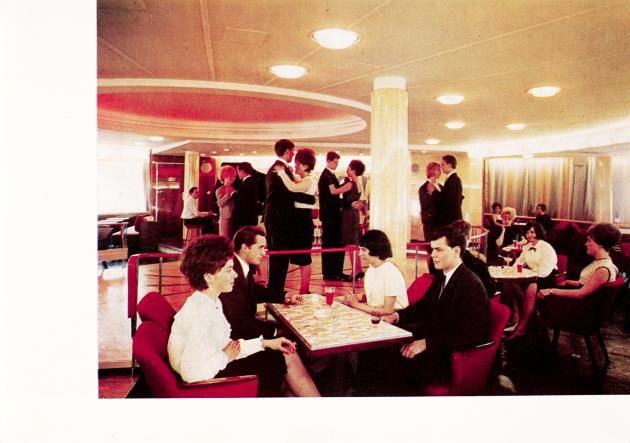

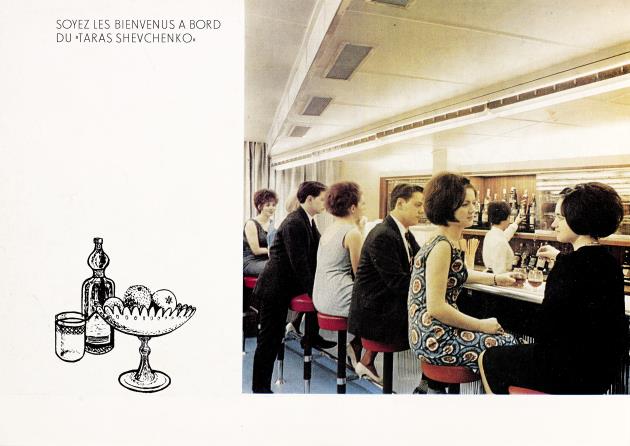

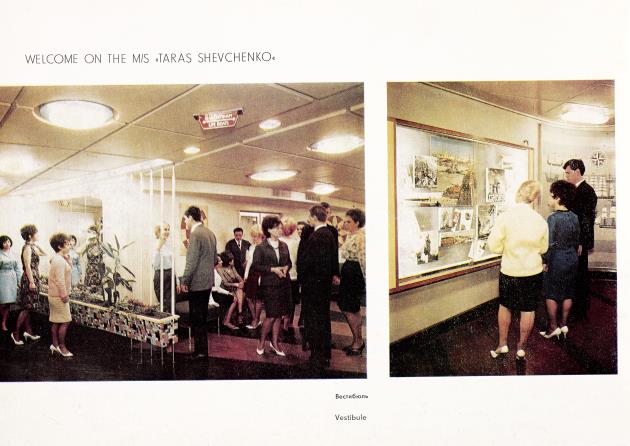

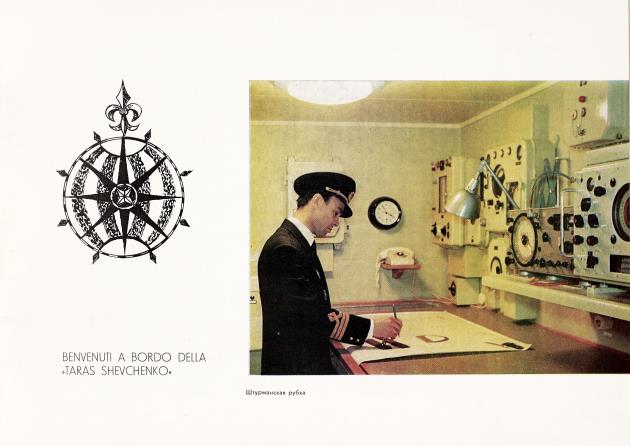

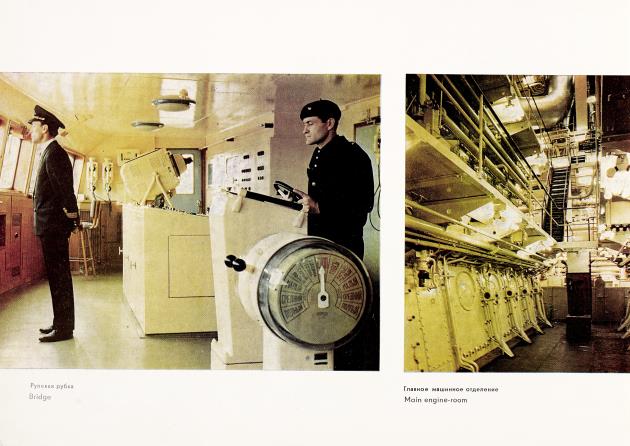

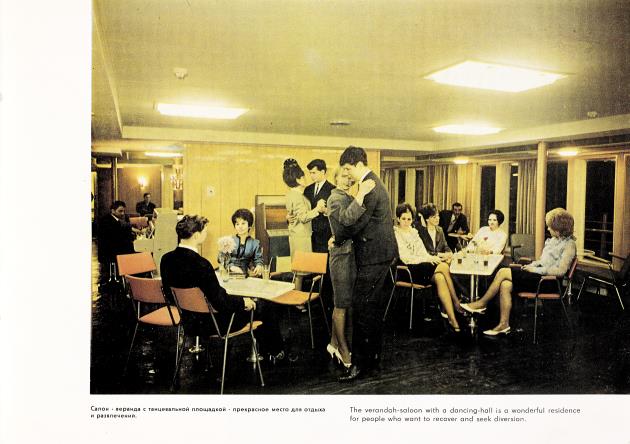

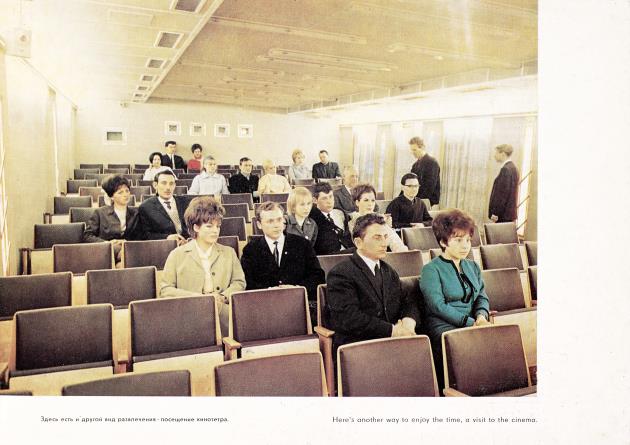

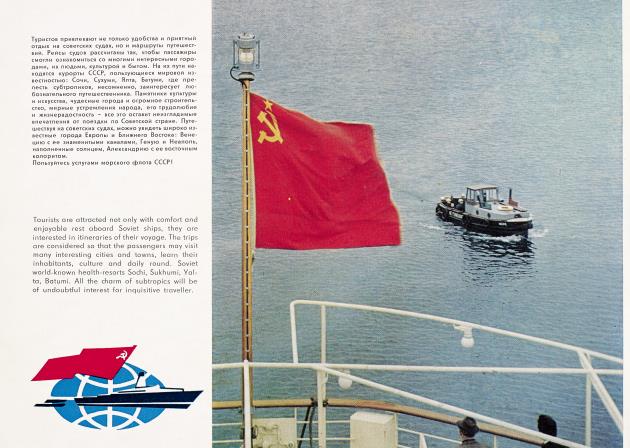

An East-German-produced travel brochure of the Taras Shevchenko

from the late 1960's (judging by hairstyles)

By Western standards the Soviet cruise products were unmistakeably budget cruise products. Considerably less expensive than comparable Western products but you had to be OK with smaller cabins, possibly no private facilities and considerably less glitz and glamour. The decor was fine and functional, but somewhat tame and lackluster in comparison with Western ships. The onboard cuisine was heavy and Central European in style and little effort was made to present the food attractively. Entertainment was less 'Las Vegas' and more 'community theatre', often with Russian crew members performing traditional Russian folklore, music and dancing. The service was accommodating and efficient, though rarely personal or English-speaking. The daily cruise routine / activity program was not that different from Western ships, though distincly Russian touches would occur, like the ever-popular Vodka/Caviar tasting sessions. The Soviet international cruises occupied a very special niche in the market, a few notches down (or left, if you will) from mainstream but in its own right still plenty enjoyable and popular.

If the ships ever had a political agenda for their leisure cruises, it was very subtle. Though they were likely meant to showcase Soviet culture, nautical prowess and industrial capability in a very general way, there were by all accounts never any active propaganda or indoctrination efforts onboard. It was really all about the leisure, fun and relaxation of ocean cruising and nothing else. In that sense they were noticeably different from the domestic Soviet cruises that many of the ships engaged in during summer seasons. Domestic cruises for Soviet citizens aspired to be serious, refined and purposeful affairs with an important social and political function for the greater good. Soviet authorities viewed them as utilitarian public services that aimed to restore, invigorate and motivate the common worker for improved performance and whose social importance should not be diluted by the excessive materialism, vulgar hedonism or frivolous entertainment that characterized Western cruising. That is not to say that these cruises were not fun for Soviet citizens, but it would have been a noticeably different kind of fun from the one Western cruisers would have on the very same ships and one can only wonder what the Soviet crews that followed these ships year-round felt about this (almost) bipolar shift in atmosphere for every season reposition.

The crews were typically composed of Russians or other Soviet nationalities, primarily in the Deck and Engine Departments, but also in Housekeeping and Food & Beverage. As a rule of thumb very few of them spoke anything but Russian, so international, English-speaking staff were employed for those positions that required the most interaction with guests or an ability to communicate fluently, like for instance in Cruise Staff, Entertainment and Guest Services. So while the guests had no problem following scheduled activities on board, they would often have to resort to sign language to communicate with their cabin steward or dining room waiter for trivial requests. To man the retail businesses onboard, operators would mostly rely on international concessionaires to supply the goods, equipment and staff for onboard photo services, beauty salons, gift shops etc. so the crews were always a mixed bag of East and West when cruising internationally. For those ships that spent their years alternating between domestic Soviet cruising in summers and international cruising in winters, I have to assume those positions were manned by Soviet staff in summer.

The high-ranking Soviet officers enjoyed the most personal freedom onboard as they had proven themselves stalwart and dependable communists through long careers but the regular crew were highly restricted and constantly supervised to ensure they were not overly tempted or corrupted by the Western ideology and materialism all around them. All of them were picked because they had family or loved ones back in the Soviet Union (which classified them as ‘low defection-risk’) but never the less they were usually not allowed any shore leave in Western destinations and armed guards patrolled the ships in port to ensure no one ‘jumped ship’. Occasionally one got away though, like in 1979 when 18-year-old Russian crew member Lillian Gasinskaya slipped out of a port hole on the SS Leonid Sobinov and swam across the Sydney harbor to freedom. Crew also had to be careful who they fraternized with from the Western crew, lest the hated Zampolit (officer in charge of crew political education and ideological integrity) started questioning their ideological allegiance which could ultimately get them dismissed, if not imprisoned.

The commercial set-up of the international Soviet cruise business was such that the various Soviet shipping companies (Baltic, Black Sea, Far Eastern) would put up their ships and crews for charters with Western cruise operators. This left the Soviets in charge of nautical operations (the running of ship and crew) and the Western operators in charge of voyage planning, marketing, sales, guest logistics, onboard service / entertainment per-sonnel etc. Sometimes they would be short-term charters of a few months or even down to an individual voyage, sometimes it would be for decades. The appeal for Western operators in using Soviet ships was that the operational costs were lower than comparable Western ships – savings that could (at least in part) be passed on to guests to ensure a steady booking flow for your budget cruise product. In an attempt to gain more control of the international cruise operations, the Soviets frequently used specific Western operators that were partly owned or financed by the Soviet Union, like for instance London-based CTC Cruises or Pacific Cruise Company. I do not know enough about their financial and corporate setup to be certain, but they certainly gave the impression of ‘dummy corporations’, giving the Soviets an operating platform on Western markets and granting them more control of the cruise product.

The Ivan Franko-class were perhaps the most well-known Soviet cruise ships on the seven seas, but far from the only ones .. nor even the biggest. In the 1970’s the Soviets went on a veritable shopping spree for second-hand Western cruise tonnage. In 1973 they bought the laid-up Cunard sister liners Carmania (1954) and Franconia (1955) – both around 21.700GRT and 900 pax – and turned them into the Leonid Sobinov and Fedor Shalyapin respectively. Both ships went on to do a lot of international cruising – the Leonid S. for Far Eastern Shipping Co. and the Fedor S. for Black Sea Shipping Co. – mostly on long-term charter for UK-based (Russian-owned) CTC Cruises. In 1974 the Soviets bought the TS Hamburg from German Atlantic Line and renamed her Maxim Gorkiy – the 25.022GRT, 650 pax cruise ship took a brief detour for a film role as the fictional SS Britannic in the 1974 movie Juggernaut, before joining the Black Sea Shipping Co. where she would spend most of her career on charter to West German travel agencies (with Phoenix Reisen for a good 20 years). The following year the Soviets bought yet another Western ship – a brand new 13.758GRT, 555 pax build from the financially overextended A/S Nordline became the MS Odessa in the Black Sea Shipping Fleet and a particular guest favorite on the seven seas.

Along with these bigger and more iconic ships, the Soviets also employed various smaller liners of the Mikhail Khalinin-class and some of the Belorussiya-class and Dmitriy Shostakovich-class cruise ferries (post full-cruise conversion) cruising the seven seas. I do not know exactly how many cruise ships the Soviets had sailing internationally from the 1960’s to the 1980’s but considering they were operating one of the largest merchant fleets in the world, it would have been substantially more than any Western cruise line of the time.

One running joke about Soviet cruises was that 1 in 4 crew had no affiliation with any Soviet intelligence agency - a joke from the ‘It’s funny because it’s true!’ realm of wit. Soviet state and military intelligence did have many agents and informants onboard – the ships provided a perfect platform for agents to observe and record civilian and military infrastructure in the many ports of call, spy on naval activity, spy on the Western guests and, for good measure, spy on their fellow shipmates to make sure they toed the party line. Rumors abound about the level of spying, bugging and foreign intelligence agent recruitment that took place onboard and about the many clandestine midnight, mid-ocean encounters with Soviet fishing vessels (= spy ships) and submarines. Despite this reputation the Soviet ships remained, if not 'welcome', then at least 'allowed' in most western ports, though most port authorities usually knew better than to assign them a berth right next to a naval base.

In their unique position smack dab in the middle of the Cold War seascape, the ships could not help but occasionally be swept up in larger geopolitical cloak-and-dagger stuff, like that time in 1975 when ‘someone’ placed two limpet mines on the hull of the Maxim Gorkiy during a stop in San Juan. The mines exploded at sea, en route to New York, but did not sink the ship and caused no casualties, but a culprit or a motive was never officially identified. Or that most suspicious incident in 1986 in which an experienced New Zealand harbor pilot seemingly with full intent ran the Mikhail Lermontov on to a well-known, precisely charted, lighthouse-marked reef in broad daylight, causing a total loss of the ship (and the death of one crew member), only to then walk away with no legal repercussions whatsoever. A politically motivated ‘hit’ on a perceived Soviet ‘spy ship’ orchestrated by Western intelligence services? Who knows? Have your pick at the conspiracy buffet! Sometimes more clear-cut political issues would impact the Soviet cruise fleet too. Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Soviet cruise ships found themselves barred from all US ports (and those of many US allies too) as part of the American embargo. The one geopolitical factor that consistently worked in their favor though, was that Soviet ships were always able to call in Cuba when Western ships were not.

Despite tensions often running high between the Soviet Union and NATO pact countries during the Cold War, it never seemed to deter international cruise guests from going on them in any significant numbers. British, Australian, West German, French and Italian clientele were particularly frequent guests. Even a few Americans, who had been conditioned to view the Soviet Union as the main adversary to America ever since WWII, could be found cruising on the Soviet ships. As budget cruise products, they were likely preferred by guests who chose with their wallets, rather than with political convictions. Perhaps the added layer of a Western operator between the guest and the ship gave them enough of a sheen of international respectability for guests to tolerate going on a Soviet ship. But then again, other international guests genuinely and wholeheartedly loved the Soviet ships for the unique style and culture they brought to the cruising experience.

Onboard the Odessa, from a Soviet 1982 cruise brochure, Fleetphoto.ru

It all ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Former member states took control of the ships in their regions and tried to carry on the business, either in a state-run format or as privatized operations. It did not last long. The outdated, run-down Soviet fleet was no match for their modern, glitzy cousins of the West that now flooded into former Soviet territorial waters to compete with them. Within a decade most of the Soviet international cruise fleet had been sold off, laid up or scrapped and more than 30 years of international leisure cruising under Soviet banners had come to an end.

The Soviet international cruise fleet was a decidedly odd duck in cruise history: a huge cruise fleet that only partially served its own home market but also its ideologically opposed adversaries, a cruise fleet that existed primarily for the enrichment of the state (whether in foreign currency or in intelligence), a cruise fleet that operated under some very unusual political restraints but yet offered leisure products that were not politicized at all, a cruise fleet that held its own crew heavily surveilled and captive in most ports and yet let Western crew members roam on and off the ships freely, a cruise fleet that was never more than 1 far-flung conflict away from being turned into ships of war (well, that one is not that unique – Great Britain sent its cruise ships off to war during the Falklands conflict too, but that’s a story for a different time).

I started out this story as a fairy tale and I wish I could tell you that all five poets lived happily ever after in new livery and under new flags, but alas, a ship’s lifespan is only so long. The Mikhail Lermontov sank, the others were scrapped one by one … save for one who graduated from Poet to Explorer. The Aleksandr Pushkin always stayed one step ahead of the breakers, took the name Marco Polo and moved from operator to operator (from CTC to Orient Lines to Transocean Tours) before ending up with British Cruise & Maritime Voyages (CMV) for a decade, becoming one of the oldest operational cruise ships around. But eventually even her luck ran out. Following the pandemic-induced bankruptcy of CMV in 2020 she was sold for scrap and in January 2021 this last remnant of the Soviet Union's international cruise empire wound up on the beach at Alang.

It was like American cruising, but now it's gone.

спасибо за службу, поэты!

Thank you for your service, poets!

This is the fourteenth article in a series of historical retrospectives on the history of cruising prior to the industry formation in the 1960's. Although not academic papers, the articles are researched to the extent of my resources and ability and strive to be as historically factual as possible. If you enjoyed it, feel free to like, share or comment and follow me (or The Cruise Insider) for more instalments.

This was so interesting and entertaining. Thank you for writing this – it has already become a valuable source of Soviet cruise ship history itself!