Soviet Leisure I

- Jacob Lyngsøe

- Oct 19, 2020

- 14 min read

Updated: Sep 21, 2025

For more than 40 years a 'covert' cruise operation was running on the border of Europe and Asia Minor – a large one with a substantial fleet of ships taking thousands of people on leisure cruises, yet hidden from view by the Iron Curtain and Soviet isolationism. Yes, the Soviet Union operated a consolidated cruise industry long before the modern American version formed in the 1960’s, in fact they operated two distinct cruise fleets, which is why this is going to be part one of the first two-parter of Pages from Cruise History. Here first, the story of the home (cruise) fleet of the Soviet Union.

It was not geography that kept the Soviet Union (and before 1922, Russia) from becoming a major player in the history of cruising. The country has an extensive Pacific and Arctic shoreline plus convenient access points to the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea and did, from the mid-19th century onwards, develop a merchant fleet that could just as easily have taken up a sideline of cruising as its European counterparts… if the market had been there. But it wasn’t. The demographics of the Russian Empire were more peasantry than bourgeoisie and simply did not have the means to pursue leisure travel. For those elevated few who did, getting to an embarkation point was a challenge; unless you lived near a port, travel distances across the vast Russian Empire were huge and the infrastructure underdeveloped (instead Russia became an early pioneer of river cruises as this was a far more convenient way to get about, but that’s an entirely different story). Lastly, thanks to the Russian Empire’s long history of bloody conflict with neighboring countries, it was a challenge to find ports of call sympathetic to Russian visitors. For these reasons, leisure cruising did not take off the same way it did in Europe in the mid-19th century.

Early beginnings

Having said that, there is evidence of some commercial cruise operations in the Black Sea as early as the start of the 20th century but World War I (1914 - 1918), followed by the Russian Revolution (1917), topped off by the Russian Civil War (1917 - 1922) suspended those activities for a long time. But you cannot keep a good idea down and by the mid-1920’s a few small-ship cruise operations started emerging again. Still in the Black Sea, early pioneer ships like the coastal steamers Lenin (1909), the Teodors Nete (1912), or the Armenia (1928) started doing regular, seasonal cruises in between their liner schedules. However, it never amounted to much traffic and was effectively ended again with the Soviet entry into World War II. The first prolonged push into Soviet leisure cruising came after World War II and ironically came courtesy of the Soviet Union’s recently defeated foe, Germany.

The German Liners

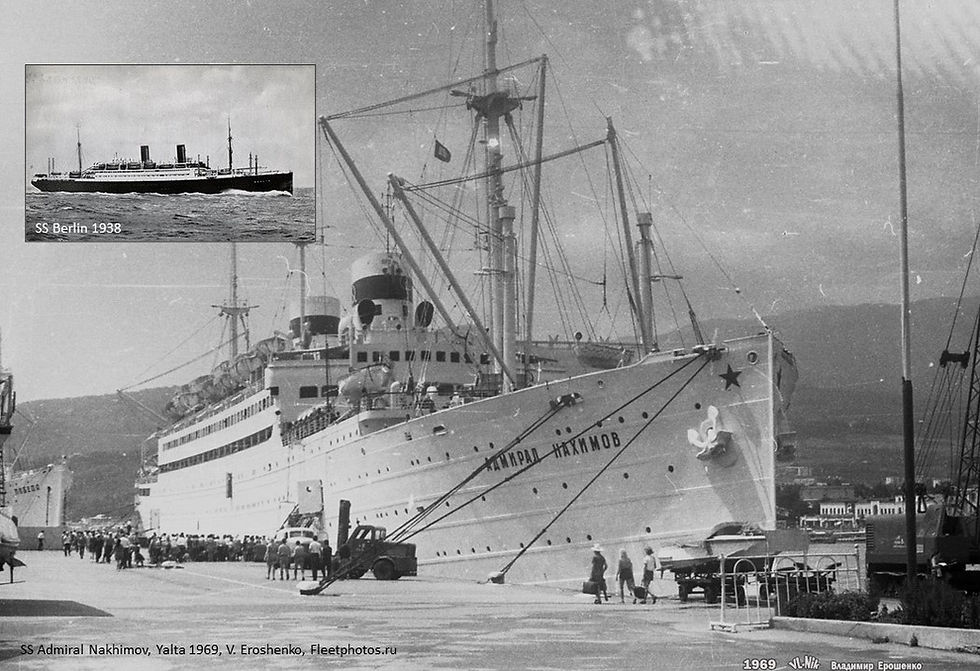

After the war a number of pre-war German ocean liners were offered to the Soviet Union as war reparations. These included ocean liners like the SS Berlin (1938, 15.300 GRT, 1.125 pax), the MS Patria (1938, 16.600 GRT, 350 pax) and the SS Magdalena (1928, 9.800 GRT, 330 pax) to name but a few. Desperately needing to replenish their merchant fleet after the horrific losses of World War II, the Soviets immediately converted and renamed the ships for inclusion into their merchant passenger fleet; The Berlin became the Admiral Nakhimov, the Patria became the Rossia and the Magdalena became the Pobeda (Victory). Despite Stalin leading the Soviet Union into its deepest phase of isolationism after WWII, there were still overseas passenger routes to ply, not to mention a lot of domestic passenger traffic across the vast inland seas of the Union, so that’s where most of the ‘old German’ ships were put to work. All three ships and others of their kin wound up under the banners of the Black Sea Shipping Company out of Odessa.

The merchant fleet(s)

All merchant shipping in the Soviet Union was under the control of the Ministry of Merchant Marine (Morflot) in Moscow and divided into different ‘company fleets’, each centered around a specific region / seaport; Baltic Sea Shipping Company was located in Leningrad (present-day St. Petersburg) and controlled the Russian merchant fleet of the Baltic, the Murmansk Shipping Company controlled the Arctic Sea fleet, Far East Shipping Company in Vladivostok controlled the Sea of Japan / Western Pacific fleet and so on and so forth (all told about 16 of them). It bears reminding that since the central command economy of the Soviet Union was based on state ownership of all assets, these should not be thought of as ‘companies’ in any commercial sense, but rather as administrative units in the state bureaucracy. One of these – indeed one of the largest of these – was the Black Sea Shipping Company in Odessa and it was out of here that most of the Soviet Union ‘home cruise fleet’ operated.

The Black Sea

Of the Soviet Union’s many inland seas and coastlines, the Black Sea was the most ideal cruise region as it offered short cruising distances, warm-water ports, a range of different Soviet or pro-Soviet destinations with varied cultural backgrounds and a pleasant continental / subtropical climate – at least in summer cruise seasons (mid-April – October). It was the perfect area to operate leisure cruises for the Soviet Union Everyman without fear of defections (which was a real and ever-present risk for any Soviet vessel going international). These cruises were typically no longer than 6-10 days and would operate out of Odessa sailing to popular ports of call like Sevastopol, Yalta, Novorossiysk, Sochi, Batumi (Georgia), Constanta (Romania), Varna (Bulgaria) and Nessebar (Bulgaria). I have found no evidence that such cruises ever visited Turkish ports despite it being the only Non-Soviet nation bordering the Black Sea but that is hardly surprising - the Turkish-Russian relationship soured during World War II and was further strained by Turkey's rejection of Soviet influence on the Bosporus Strait and the countrys subsequent acceptance into NATO. In Soviet eyes, Turkey was 'the West' and a no-go.

The workers' cruise

The clientele for these early Soviet cruises were the average working class – in fact there are quite a few parallels to be drawn to the German cruises of the 1930’s under the National Socialist ‘Kraft Durch Freude’ organization (read Hitler’s Holidays), in as far as Soviet cruises were also state-operated and heavily subsidized to enable worker participation, also featured a strong ideological slant and mostly only visited ideologically sympathetic destinations. Like the Nazis, the Soviet state also tended to view the purpose of the cruises (or indeed, of holidays in general) as strictly utilitarian – something that served to recharge, strengthen and motivate the common worker for improved performance, rather than an as a reward or as an opportunity for idle leisure. Just like in Germany the ships found an appreciative and adoring clientele with the common worker who had just endured the horror and hardships of World War II and had likely never travelled for leisure (certainly not to sea) before. While they may have been outdated, patched-up, German prizes of war that paled in comparison with their newer Western counterparts, to the Soviet guests they were floating palaces full of wonder, adventure and fun.

In the post-war era, Soviet workers were entitled to two weeks paid vacation and most chose to take one of the holiday options provided by the state, whether it be one of the prevalent choices, like a therapeutic and regenerative stay at a sanatorium, a physical and invigorating active holiday out of a rented Dacha (holiday cottage) or – in this case – a relaxing and exploratory cruise on the Black Sea. The travel logistics were handled by government-owned travel agencies, and were always based on group travel, not just for efficiency of cost and logistics, but also to promote solidarity and facilitate state surveillance (which was an inescapable aspect of Soviet life). So instead of a mixed passenger complement from all over the Union, it is much more likely the ships would have carried multiple groups from geographically specific locations.

Soviet cruise experience

Due to an overall scarcity of online sources from this period of Soviet history and the indecipherability of Cyrillic letters to me, I am left without much detail about this Soviet ‘home cruise fleet’. I have found clues to suggest that it started as early as the late 1940’s, initially only on the ‘old German’ liners, now flying the flag of the Black Sea Shipping company and taking breaks out of their regular summer schedules to operate leisure cruising, but I do not know exactly when or with how much frequency or volume. In my research I had expected to find that the ships would be single-class and not particularly luxurious, since Soviet dogma generally idealized classlessness and denounced luxury as a decadent symptom of Western materialism but several references and brochure materials indicate the opposite was true. There seems to have been 1st, 2nd and 3rd class cabin categories throughout the Soviet cruise era (ranging from sumptuous deluxe cabins with in-cabin facilities to spartan bunk-bed cabins with shared facilities) and while you can argue about taste, there is no denying that many of the public areas were indeed plush and luxurious for the time.

1950 brochure pictures from the Rossiya seems to indicate an eclectic mix of luxury and austerity

as well as different cabin categories, © Seven_Balls / FleetPhotos.ru

I also do not know much about the ‘tone’ of these cruises, except to speculate that they would have been decidedly different from that of Western cruises. As mentioned, the ‘party line’ was that the people’s vacation had to be purposeful; it had to serve the recuperative rest of workers so that they may return to work rested, healthy and more productive, or be characterized by physical activity to promote the strength and stamina of workers, or it had to serve the exploration and appreciation of the Motherland to boost the pride, love and loyalty of the worker. Most importantly of all it had to distinguish Soviet leisure from the vulgar, materialistic vacationing habits of the West, what with their decadent luxury, hedonistic excess and frivolous relaxation.

That put the Western cruise experience (and the American in particular) worlds away with its ‘eat, drink, make merry and keep spending’ philosophy and probably by comparison gave Soviet cruises a more disciplined, austere and no-nonsense character. How exactly that manifested itself onboard, I cannot say; perhaps more lectures and less entertainment, perhaps more focus on physical exercise and less on all-you-can-eat-buffets, likely more focus on group activities and solidarity than individual pursuit of leisure. That is not to suggest that Soviet cruise guests did not have fun onboard or did not enjoy their vacations thoroughly - just like their Western counterparts the ships had restaurants, bars, lounges, cinemas, theaters, libraries, pools, gyms (not sure what the Soviet position on casinos was, but I am guessing 'not') etc. and guests enjoyed good food, plenty of vodka and plum brandy, onboard entertainment (of the home-grown and government-sanctioned kind) and varied activities. Of course there was fun and enjoyment to be had. I just cannot shake the notion that knowing that not only was there a pronounced ideological agenda from 'Big Brother' to your leisure time, there were likely also agents of the state onboard to ensure that everyone toed the party line – that just had to have made for a special kind of atmosphere on board.

The Soviet 'Titanic'

What I do know is that Soviet cruising operations in the Black Sea continued and expanded from this point on. The ‘old German’ liners were hugely popular and hung in there for a surprisingly long time (although I have to assume, they underwent some renovations along the way). The Pobeda did not retire until 1979 (aged 51) and the Rossia stayed in the cruise game until 1985 (aged 47). The Admiral Nakhimov did not make it to retirement. She became the largest peacetime maritime disaster involving a cruise ship that you have never heard of. In the evening of 31 August 1986, while departing the port of Novorossiysk, the Admiral Nakhimov collided with the bulk carrier Pyotr Vasev, rolled over and sank within minutes, taking 423 out of 1.234 passengers and crew to their deaths. Why is that not common knowledge? Because 1986 was the summer of Chernobyl and very few news headlines from the Soviet Union made it past the glowing, radioactive mess that was Chernobyl. Besides, while Mikhail Gorbachev had recently initiated Glasnost - the policy of openness and honesty in Soviet foreign relations - old-school Soviet apparatchiks were not about to reveal such a calamitous and embarrassing disaster to the West, especially since it was the result of blatant human error on the part of the Soviet maritime officers. So the Admiral Nakhimov not only disappeared from the surface of the Black Sea but from the pages of history as well.

Fleet growth and development

The old German ships were eventually supplemented by newer vessels but it is very difficult to produce a comprehensive list of which ships eventually joined the home cruise fleet of the Black Sea. Absent a clear commercial agenda for the ships, they would move about between fleets/region on a (Communist party) whim, change function (or name) for political objectives, get sent overseas for charter roles in the Western cruise industry or just ‘disappear’ for a while because the state needed a vessel for some unnamed political/military purpose (they were frequently used for troop transport in overseas conflicts). This plus the absence of digital records from the era makes tallying the fleet as challenging as counting a flock of birds in flight but just to give you some idea of the growth and development of the fleet: No fleet additions happened under the isolationist reign of Stalin, but after his death in 1953 his successor Nikita Khrushchev opened up for relations to the outside world and started new shipbuilding programs that would eventually grow the Soviet merchant fleet into one of the biggest in the world.

Fleet additions

One such program was the Mikhail Kalinin-class coastal liners/cruise ships, ordered with the East German shipyard VEB Mathias-Thesen in the mid-1950’s. Of the 19 ships produced under this program quite a few went to the Black Sea Shipping Company (the Litva, the Adjaria, the Armenia, the Adzhariya and the Bashkiriya are just the ones I have been able to pin down by name) and took up seasonal cruising. These were relatively small ships between 4.800 and 6.100 GRT with room for only 330 pax but they became quite popular and moved a lot of guest volume in their time thanks to the relatively short itineraries. In the 1960’s the Soviet Union felt the need to prove to the West that they could build large, majestic ocean liners as well as any Western country (despite the fact that ocean liners were already losing out to air travel) and they commissioned the Ivan Franko-class from East Germany.

Of the five 19.860 GRT liners launched between 1963-1972, three of them went to the Black Sea Shipping Company – the Ivan Franko (1964), the Taras Shevchenko (1967) and the Shota Rustaveli (1968). Their liner service turned out brief, bordering on non-existent, but they did become enormously popular as cruise ships. Although they were meant to be state of the art and the equal of Western ships in every aspect, it is quite telling about Soviet passenger fleet standards in the late 1960’s that half the cabins did not even have private facilities – something no Western shipping company would have practiced at the time.

The 1970’s did not see any new classes of liners/cruisers being built, but instead saw the introduction of the cruise ferries - the MF Belorussiya the MF Kareliya and the MF Azerbaydzhan all operated cruise/ferry service out of Odessa from the mid-70’s to the mid-90’s. They were all sisters from a class of five cruise ferries (Belorussiya-class), built in Finland in 1975, with a berth capacity of around 500 guests and room for 250 cars. The designation ‘cruise ferry’ makes it likely that they initially served mostly in ferry capacities with overnight passage, but as of the mid-1980’s all three were converted to cruise ships proper and had their car decks converted into passenger decks.

The fall of the Soviet Union

By 1990 the Black Sea Shipping Company was the largest shipping operator in Europe and the second-largest in the world, but in 1991 the world changed. With the fall of the Soviet Union, the company passed under Ukrainian state control and was rebranded BLASCO. As the Soviet Union fell away and the individual member states opened up to Western tourism, the international cruise lines caught on to that most attractive quality in destinations; Virgin Waters! Destinations previously unseen, sights formerly denied to Western eyes, a peek behind (what was once) the Iron Curtain – the same lure that made St. Petersburg the undeniable highlight of every post-Soviet Baltic cruise, now drew a steady stream of Western cruise ships into the Black Sea.

The geographical and navigational conditions of the Bosphorus Strait (the only access to the Black Sea from the Mediterranean) ensured that only small and midsize ships got to explore this new region and the behemoths had to stay out. So for a while ex-Soviet and Western cruise ships mingled freely, but not for long. Whether poorly managed or unable to compete in free market economics, the Black Sea Shipping Co. soon ran into an escalating series of legal issues and financial instabilities culminating in a declaration of bankruptcy in 2009. Whatever ships remained in the fleet at that time were sold off, scrapped or re-purposed and the last remnants of the Soviet cruise empire scattered to the winds.

Russia remains to this day one of the biggest markets for river cruising (a subject just outside my area of expertise), but has not made any attempt to rebuild a high seas cruise fleet … so far. However, rumors are swirling that Russia’s largest state-owned shipbuilder, United Shipbuilding Corporation, is contemplating a fleet of medium-sized, luxury expedition ships for the Arctic Sea – a popular area for expedition cruising that Russia has unique access to and experience with - so let's just stick a pin in that for now.

‘But hang on! You said to begin with that there were two Soviet cruise fleets!

What about the other one?’

That’s right – I haven’t even gotten to the International Fleet, but I will … in the next installment of Pages from Cruise History.

Author’s note: Oh boy, and I thought researching cruise history was hard enough to begin with – try moving the focus of your research behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War. Verified and reliable sources on this piece have been very hard to find – very few have bothered to digitize old records or detail the story of this particular corner of Soviet leisure travel and I have been left to piece together an overall picture based on pop culture snippets, ship enthusiast sites and research on Soviet shipping and vacation, augmented by deduction and conjecture. Although I feel fairly sure that I have painted a truthful (if incomplete) picture, I still feel like this is the ‘airiest’ piece I have done on cruise history, so if all you take away from this is that the Soviet Union operated leisure cruises from World War II until the fall of the Soviet Empire and that they were very different from their Western counterparts, then that is OK. I will revisit this piece and flesh it out the day I come across some reliable sources – if you, Dear Reader, know where to find these, please let me know.

This is the thirteenth article in a series of historical retrospectives on the history of cruising prior to the industry formation in the 1960's. Although not academic papers, the articles are researched to the extent of my resources and ability and strive to be as historically factual as possible. If you enjoyed it, feel free to like, share or comment and follow me (or The Cruise Insider) for more instalments.

Comments